- Home

- Jana Reiss

Flunking Sainthood Page 7

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 7

It was a mystery to me why Margaret wanted the surgery. She already looked years younger than her age, thanks to healthy living and a number of smaller procedures and Botox injections. She was one of the most beautiful women I knew, and frankly I was a little in awe of her. But she was never satisfied with her looks. I hoped that this major face-lift would be the last of her attempts to stave off the inevitable aging process, but I had my doubts.

There are two ways to get enough: one is to continue to accumulate more and more. The other is to desire less.

—G. K. CHESTERTON

That evening, I read a novel and puttered around Margaret’s house while she slept off the anesthetic. How I loved her house. She had, as a single woman, been able to purchase a veritable mansion that had ties to one of the city’s early entrepreneurs, a testament to Margaret’s own financial success and to Cincinnati’s reasonable real estate prices. It was a gorgeous house, with original woodwork, a well-appointed kitchen, a spacious formal dining room, and six bedrooms. Margaret had a flair for interior decoration, and every room bespoke her impeccable taste.

Yet she was always buying things. When we would get together, usually for lunch or to catch an artsy movie, the conversation often turned to some new purchase, often an extravagant one. She had an account at one of the city’s finest furniture shops and was forever shopping for elegant dressers, rugs, and paintings. However, her joy in each new purchase was short-lived, and she often complained of problems with designers and tradesmen. The drapes, delivered at long last, were several inches too short; the custom-designed stained glass windows contained too much yellow, her least favorite color.

I never see Margaret anymore. We parted awkwardly after a quiet disagreement, and she never called me again. I still think about her often and I miss her company; she was funny, smart, and very interested in art and music. But her soul seemed unexpectedly discontented with her life and its cast of characters, always peering beyond her present situation to the next purchase, the next makeover. She was surrounded by beauty, but seemed incapable of appreciating it for long. She wanted—thought she needed—more.

Although it’s hard to admit, I see a good deal of Margaret’s restlessness in myself. I feel clear-sighted enough to diagnose and judge materialism in a former girlfriend, but wasn’t I the one wandering around her house sighing with pleasure at all the pretty things? I was often envious of Margaret’s house, books, art, and yes, her freedom as a single woman to do pretty much as she pleased. I’m no more ready than Margaret to implement Richard Foster’s wise counsel about how real simplicity begins when we stop looking to the outside world to validate our existence:

Perhaps no work is more foundational to the individual embodying Christian simplicity in the world than our becoming comfortable in our own skin. The less comfortable we are with ourselves, the more we will look to things around us for comfort. The more assured we are with ourselves, the less assurance we will need from things outside us.

COVETING AND THE PROBLEM OF CHOICE

My secret longings for Margaret’s beautiful house bring me to the crux of my spiritual practice this month: The problem isn’t shopping. The secret problem is coveting.

My name is Jana and I am a coveter. I like fantasizing about trips I’ll take all over the world, and I envy people who have the wherewithal to travel. I envy other women’s svelte figures, even though I’m too lazy to do the exercise that could ever result in that physique. And I buy into a culture and an advertising industry that rest upon the bedrock notion that people can and should be made to want what they don’t yet have. Not coveting would be downright un-American.

I decide to explore what the Bible has to say about coveting, discovering what I suspected: coveting is not exactly encouraged. In the Ten Commandments, the Bible calls attention to the “do not covet” commandment by repeating it. That’s because in the Hebrew language, there’s no easy way to signal emphasis. You can’t italicize or underline anything, like you might in English, and there’s no such thing as an exclamation point. You can’t say, “God really wants you to keep this commandment in particular!” What you can do is repeat it, because in Hebrew, if it’s worth saying once then it’s worth saying seventeen times. So in the Bible, the last commandment is rendered “Thou shalt not covet, thou shalt not covet,” and it’s the only one of the Ten Commandments that merits double billing. Here’s the text from Exodus 20:

You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or male or female slave, or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor.

This month’s spiritual practice of not shopping has led me to a deeper underlying issue: now I have to try not to covet. In fact, every spiritual practice I’ve attempted so far has resulted in failure not because I didn’t adhere to the basic requirements of each experiment—I didn’t cheat on my fast or neglect to listen to the Gospel of Mark, for example—but because the practices started pointing me to more profound issues below the surface that I couldn’t quite face. I kept the fast, but I realized midway through that I was fasting for the wrong reasons. I was as worldly and selfish on February 28 as I’d been on February 1. With lectio divina, I adhered to the letter of the law, but never allowed myself to be vulnerable to the Bible’s claims on my life. Where I was once too quick to imagine the Bible’s words as direct answers to my prayers, now I’m reluctant to trust the book again.

I have learned, in whatever state I am, to be content.

—THE APOSTLE PAUL (Philippians 4:11)

This month I’m determined to dig beyond the superficial practice of not shopping to the underlying, and much more difficult, practice of not coveting. When I have to order a book for work through Amazon—I need it for business, really!—I try to whiz past the site with blinders on, ignoring all of Amazon’s well-timed recommendations for my weakest spots. If you liked Settlers of Catan, you’d be sure to enjoy every other board game the company has ever made! If you bought a lawnmower on Amazon [guilty], you must need a weed whacker too!

I wonder if coveting is worse in the twenty-first century since we’re presented with an unprecedented number of choices. In 1949, the average American grocery store carried 3,750 items; today that number is near 45,000. Half a century ago, you might have walked to your little downtown bookstore to find a small selection of a couple thousand titles; today, there are twenty-four million books listed on Amazon.com.

According to some psychologists, all this choice comes at a cost. Sheena Iyengar’s research on choice started when she was a graduate student and used to go to a big weekly market in the Bay Area. Despite the vastness of the market (250 types of cheese!) and her own gourmet tendencies, she hardly ever bought anything there. On a hunch, she decided to try an experiment that wound up becoming the basis for her career research and later the book The Art of Choosing: she set up a table at the market with samples of jam. When she offered six varieties of jam in a taste test, 30 percent of the customers who tried the jam went on to buy a jar or two. When she put twenty-four varieties on her sample table, she had more floor traffic of people stopping by for a taste, but far fewer actually made a purchase—only 3 percent went on to buy a jar of jam. The lesson Iyengar learned from this seemed counterintuitive: there is such a thing as too much choice. It turns out that we get overwhelmed easily.

It’s not just in consumer behavior that we have a dizzying array of selections. We now enjoy unprecedented choice in how we arrange our families, space our children (or have them at all), decide on a major, or even find a religion. In past generations, our religious affiliation was mostly decided for us by our parents (if you’re born a Lutheran, you are a Lutheran; pass the hot dish) or limited by simple geography. One of Iyengar’s long-term experiments questions whether having more choice in matters of religion makes people happier. It doesn’t. Surprisingly, the religions that claim the happiest people are those that make some of the decisions for you by removing certain choices; the unhappiest peop

le belonged to the most open-minded and tolerant faiths. Reform Jews and Unitarians were the most susceptible to depression, while fundamentalists faced adversity with optimism and experienced greater hope. It turns out that limits are often very good things.

When I ponder this, the point of this month’s practice hits me: it’s not just about curbing materialism, though that’s a good thing, or even about not coveting. It’s about taking some choices out of the mix, of letting God’s guidance dictate the basic contours of what I will and won’t do. I’m not just reducing physical clutter by not shopping; I need to reduce spiritual clutter by becoming the kind of Christian who does not covet. I’m going to get off the more, more, more treadmill and set spiritual limits in order to cultivate simplicity. Eureka!

But shortly after this epiphany, here is the thought that hits me: I really like that Richard Foster guy, and want to read all of his books. I can’t wait for May to be over so I can buy them.

6

June

look! a squirrel!

A monk when he eats, drinks, sits, officiates, travels or does any

other thing must continually cry: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God,

have mercy on me!” so that the name of the Lord Jesus, descending

into the depths of the heart, should subdue the serpent ruling over

the inner pastures and bring life and salvation to the soul.

—THE PHILOKALIA

School’s out, so why am I feeling so frazzled? The sudden absence of homework has made for a happier child and two parents on temporary furlough from their quarter-time jobs of sitting at the kitchen counter to supervise long division. My work is going well, except that there’s too much of it. Multiple deadlines and a string of travel have left me exhausted, and an unexpected summer sinus infection, mild but annoying, plagues me as I go about my business. They’re all minor complaints, and I even feel guilty for having them, but the end result is a run-down and irritable me.

“Enervated,” I say to Phil one day. I am enervated. The term itself seems a cruel joke—a word that should be “energized” but took a sudden turn to the dark side to zap everybody’s juices.

What might help, I hope, is this month’s spiritual practice: contemplative prayer, about which I have long been curious. I’ll start with Centering Prayer, which is one way of doing contemplative prayer. Open Mind, Open Heart, Thomas Keating’s classic book on the subject, is my assigned reading for June. He spends a good deal of time on the notion that contemplative prayer has always been an integral part of Christian spirituality—the book’s subtext being that Father Keating didn’t just make it up one day. His early descriptions lure me to the practice: “Centering Prayer is a discipline designed to reduce the obstacles to contemplative prayer,” he explains. “Its modest packaging appeals to the contemporary attraction for how-to methods.” Sold! This sounds like the kind of guide I had hoped for from Brother Lawrence back in March. Father Keating wants me to take twenty minutes a day to sit in silence and open myself up to God. Surely even I can manage twenty minutes of contemplation.

Centering Prayer isn’t like the kinds of prayer most Christians are used to, where we petition God for things, like good health or greater understanding. Or a new laptop—not that I’d know anything about praying for that. The practice focuses on being still, turning to what Keating calls “a fuller level of reality” that’s always around us but that we often don’t notice amidst the usual chaos of our lives. I’m in full agreement with the basic goal: that we stop yammering to God about our petty concerns and take the time to listen.

We need to shut up. I need to shut up.

Pause for a moment, you wretched weakling, and take stock of yourself: Who are you, and what have you deserved, to be called like this by our Lord?

—THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING, 13th century

I’d like to use Keating’s book to get started with Centering Prayer, but despite the early promise of a how-to approach, it quickly becomes too theoretical for my taste. Plus there is a weird section in a Q&A portion of the book where a reader asks Keating, “Does my guardian angel know what goes on in my Centering Prayer?” It’s news to me that I even have a guardian angel, let alone one who’d be snooping in my deepest prayers, and the idea creeps me out. So after a good skim of the Keating book I put it aside in favor of Cynthia Bourgeault’s more accessible and down-to-earth guide Centering Prayer and Inner Awakening, which my editor recommended.

Bourgeault begins by posing the question, “Why do we need yet another book on Centering Prayer?”

A: “Because Jana didn’t understand the first one she read.”

Well, Bourgeault doesn’t say my name specifically, but she does politely hint that I’m not the only one who found the book by Thomas Keating—her own teacher, as it happens—too lofty. I’m heartened by the author’s admission that it took her many years to fix on a contemplative prayer practice; she’d been an Episcopal priest for a decade already before she discovered Centering Prayer. Maybe I have a shot at this.

Here is what Bourgeault says about getting started:

It’s very, very simple. You sit, either in a chair or on a prayer stool or mat, and allow your heart to open toward that invisible but always present Origin of all that exists. Whenever a thought comes into your mind, you simply let that thought go and return to that open, silent attending to the depths. Not because thinking is bad, but because it pulls you back to the surface of yourself. You use a short word or phrase, known as a “sacred word,” such as “abba” (Jesus’ own word for God) or “peace” or “be still” to help you let go of the thought promptly or cleanly. You do this practice for twenty minutes, a bit longer if you’d like, then you simply get up and move on with your life.

It sounds like a cinch, doesn’t it? I appreciate the fact that Bourgeault opens with this section on how to do Centering Prayer, rather than merely what it is. I like the hands-on approach, and for the first few days I slowly read the book and try the practice for twenty minutes at lunchtime. But while Bourgeault’s book is infinitely clearer to me than Keating’s, in a way that makes it worse: I can see all too clearly now that I am going to fail. Here are some things that she tells us not to do when practicing Centering Prayer, all of which I am doing or have done:

Effortlessly, take up a word, the symbol of your intention to surrender to God’s presence, and let the word be gently present.

—M. BASIL PENNINGTON

• Don’t assume that silence is something to be filled up. Don’t think of God as a “content provider” who spills urgent messages into your addled brain the moment there is a little silent space for him to do so.

• Don’t repeat your sacred word like a mantra. It’s just a placeholder in case you need to refocus your attention. (Oh.)

• Don’t evaluate how you’re doing midstream as if this were a judged Olympic performance.

• Don’t resist a thought, retain a thought, or react to a thought.

• Don’t fall asleep.

• Don’t listen, don’t think, don’t pray. (Wait . . . wasn’t praying precisely the point?)

Already I’m screwing up, and it rankles. I am not enjoying this practice, not even to cherish the sensation of having twenty minutes a day to not pray/not listen/not think. I can’t seem to focus my mind, and it’s driving me bonkers.

One day early in June I sit in our living room to undertake my Centering Prayer practice. I’ve already set the kitchen timer for twenty minutes, so I’m ready to roll. I sit down on the ottoman, which is backless and therefore not very comfortable. I figure I get at least two holy brownie points for that. The phrase I’ve chosen for my sacred non-mantra is “peace, be still.”

The first thing I notice is the sudden noise around me. It’s lunchtime during the first Wednesday of the month, and I’d forgotten that it’s siren day. At noon on that day, the city of Cincinnati always tests its emergency siren system. Waaaaaaaaaaaaaaail. I wonder what would happen in a real emergency,

speculates Monkey Mind. What kind of situation would they use this siren to tell us about? Just a tornado, or a terrorist attack? Oh crikey, what would I do in a terrorist attack?

“Peace, be still,” whispers Spiritual Mind. I let it go. I picture that thought floating away on a sailboat, stark against a bright blue sky. I hear a dog bark. A toddler fusses on the sidewalk outside.

You know, it would be quieter in this room if we replaced those eighty-five-year-old windows with double panes, suggests Monkey Mind. That’s a really good idea! I have been meaning to research that possibility. How much would it cost, though? Would we be able to afford it while also paying for Jerusha’s new school for next year? Could we match the old six-over-one window panes, or do they not make that style anymore?

“Peace, be still,” says Spiritual Mind, a little more firmly this time.

I sigh and try to listen for God. Or maybe that was God, interjects Monkey Mind. Maybe God is telling you to replace the windows and do your bit for the environment. Newer windows are so much more energy efficient. God cares about creation, you know!

“Peace. Be. Still.”

We start again. Peace is such a beautiful thought. Peace, be still, hums Monkey Mind. What are the lyrics to that hymn? “The winds and the waves shall obey Thy will, Peace, be still! Whether the wrath of the storm tossed sea, Or demons or men, or whatever it be. . . .” Hey, did the guy who wrote that hymn really think that demons were attacking him? That is so bizarre. What would that feel like, if demons were real and they just went around attacking people? What if a demon tried to possess me like in that movie where—

“Shut the hell up!” yells Spiritual Mind.

I’m starting to understand what the phrase “spiritual warfare” is all about. As the days wear on, “Peace, be still,” verges on a spiteful joke. I am not getting this. I begin coming up with every kind of excuse to avoid the practice. During my lunch break when I’ve planned to hunker down and just do it, I realize that Onyx has not yet been walked today. I’m sure he desperately needs to get some fresh air and check his pee-mail from other dogs in the neighborhood. Shouldn’t I take care of that first? And when we return from that, there are only forty minutes left in my lunch hour. If I spend twenty of those minutes doing Centering Prayer, I’ll only have twenty minutes left to make and eat my lunch. Hmmm. Don’t those mindfulness teachers also say that you should never eat in a rush?

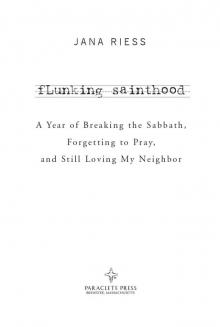

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood