- Home

- Jana Reiss

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood Read online

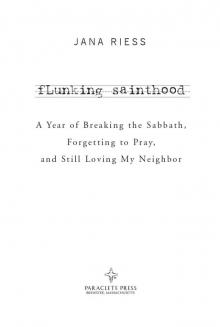

fLunking sainthood

A Year of Breaking the Sabbath,

Forgetting to Pray,

and Still Loving My Neighbor

ADVANCE PRAISE

“So many books make the history and practice of Christian spirituality dreadfully boring through their earnestness, but Jana Riess brought a smile to my face on page one! Flunking Sainthood is a witty memoir of a year of failing—and therefore, paradoxically, succeeding—at putting Jesus first. Would that we all failed so well.”

—Tony Jones, author of The Sacred Way: Spiritual Practices for Everyday Life

“Who would have guessed that trying and failing at the spiritual disciplines is way better than not trying at all? And—here’s the real surprise: it may even be better than trying and feeling like a success. Flunking Sainthood guides you into the human side of the spiritual life with good humor and a bathtub full of grace.”

—Brian McLaren, author of Naked Spirituality: A Life with God in 12 Simple Words

“Warm, light-hearted, and laugh-out-loud funny, Jana Riess may indeed have flunked sainthood, but this memoir assures us that she is utterly and deeply human, and that is something even more wonderful. Honest and sincere, she will endear you from page one.”

—Donna Freitas, author of The Possibilities of Sainthood

“Flunking Sainthood allows those of us who have attempted new spiritual practices, and failed, to breathe a great sigh of relief and to laugh out loud. Jana Riess’s exposé of her year-long and less-than-successful attempts at eleven classic spiritual practices entertains and educates us with its honesty and down-to-earthiness. She writes in the unfiltered, uncensored way I’d write if I had the skill and the guts.”

—Sybil MacBeth, author of Praying in Color

“Jana Riess’s new book is a delight—fun, funny, engaging and a powerful reminder that the greatest work in our lives is not what we’ll do for God but what God is doing in us.”

—Margaret Feinberg, author of Scouting the Divine and Hungry for God

“Jana Riess proves to be a standup historian well-practiced in the art of oddly revivifying self-deprecation. This book is freaking wonderful—a candid and committed tale that resists supersizing and spirituality that has no home save the glory and muck of the everyday.”

—David Dark, author of The Sacredness of Questioning Everything

JANA RIESS

fLunking sainthood

A Year of Breaking the Sabbath,

Forgetting to Pray,

and Still Loving My Neighbor

Flunking Sainthood: A Year of Breaking the Sabbath, Forgetting to Pray, and Still Loving My Neighbor

2011 First printing

Copyright © 2011 by Jana Riess

ISBN 978-1-55725-660-7

Unless otherwise designated, Scripture references are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked (KJV) are taken from the Authorized King James Version of the Holy Bible.

Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Riess, Jana.

Flunking sainthood : a year of breaking the Sabbath, forgetting to pray, and still loving my neighbor / Jana Riess.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 978-1-55725-660-7 (paper back)

1. Spiritual life—Christianity. 2. Perfection—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Failure (Psychology)—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Success—Religious aspects—Christianity. 5. Riess, Jana. 6. Spiritual biography. I. Title.

BV4501.3.R537 2011

248.4—dc23 2011022595

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts

www.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

FOR PHIL

my resident saint

AND FOR PAPA

who is such a blessing to us

Many people genuinely do not want to be saints, and it is probable that some who achieve or aspire to sainthood have never felt much temptation to be human beings.

—GEORGE ORWELL

contents

behind the scenes

1

January

choosing practices

2

February

fasting in the desert

3

March

meeting Jesus in the kitchen . . . or not

4

April

lectio divination

5

May

nixing shoppertainment

6

June

Look! a squirrel!

7

July

unorthodox sabbath

8

August

thanksgiving every day

9

September

benedictine hospitality

10

October

what would Jesus eat?

11

November

three times a day will I praise you

12

December

generosity

Epilogue

practice makes imperfect

Notes

A note to readers

behind the scenes

My mom is the sort of person who always wants to know how a book ends before committing to it. It’s one of the only things I dislike about her, but she’s part of a whole cadre of like-minded readers who furtively skip to the end of a book to spill its secrets before they make an emotional investment.

So for Mom, and for her silent but guilty compatriots, here is the spoiler: I am going to fail at every single spiritual practice I undertake in this book.

I didn’t set out to write a book about spiritual failure. This project originated as a lighthearted effort to read spiritual classics while attempting a year of faith-related disciplines like fasting, Sabbath keeping, chanting, and the Jesus Prayer. It culminated in a year-end meeting with my editor, Lil Copan, in which I tried to steel her for the fact that I had fallen short in every single spiritual practice I’d tried. I felt dejected—what kind of loser fails at the Jesus Prayer? I mean, it’s twelve words long and takes about four seconds to recite. Lil helped me see the value in a different kind of book, one about the wild acceptability of failure itself. She suggested the title Flunking Sainthood. I’m grateful to her for careful editing, challenging feedback, and broad vision. (Even as I write that sentence, I hear her voice in my head, telling me I’ve used excessive adjectives.) I’m grateful also to Jon Sweeney, Carol Showalter, Pamela Jordan, Sister Mercy, Jenny Lynch, and all the good people at Paraclete Press, a bright spot on the landscape of publishing.

I owe thanks to Beliefnet.com for helping me find my tribe of failed saints through the “Flunking Sainthood” blog, and to the many folks I’ve talked to at Emergent gatherings who connected immediately with the idea of finding the joy in failure. Jonathan Merkh provided invaluable help with my book contract, and many people recommended books to me, including Cynthia Eller, Bob Fryling,

and Jeanette Thomason. Jamie Noyd and Leighton Connor, members of my writing group, offered invaluable feedback on drafts, and the sisters at the Community of Jesus spoiled me with exceptional food and hospitality while I was on my writing retreat. My family deserves a medal for graciously loving me through another book.

This book arose out of conversations with many generous friends and acquaintances, some of whom you’ll meet on these pages, but especially Dawn and Andrew Burnett, Claudia Mair Burney, Rudy Faust, Donna Freitas, Nancy Hopkins-Greene, Asma Hasan, Kelly Hughes, Ron and Debra Rienstra, Scot McKnight, Lauren Winner, and Vinita Hampton Wright.

My December practice of generosity would not have been possible without the financial contributions of Christopher Bigelow, Samuel Brown, Alethea Teh Busken, Stephen Carter, Lil Copan, David Dobson, Sheryl Fullerton, Kathryn Helmers, Myra Rubiera Hinote, Kelly Hughes, Donna Kehoe, Mark Kerr, Linda Hoffman Kimball, Tania Rands Lyon, Sheri Malman, Preston McConkie, Don McKim, Jana Muntsinger, Marcia Z. Nelson, Kerry Ulm Ose, Tina Hebbard Owen, Vince Patton, Charles Randall Paul, Bernadette Price, Jana Bouck Remy, John Nakamura Remy, Phyllis Riess, Carol Showalter, Kristen Mueller Smith, Megan Moore Smith, Rory Swenson, Hargis Thomas, and Debbie Wilson Waggoner.

I hope I haven’t forgotten anyone, but this is a book about screwing up, so I give myself a pass.

1

January

choosing practices

You see that I am a very little soul

who can offer to God only very little things.

—ST. THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX

My friend Kelly went through a phase when she was about seven years old when she wanted quite desperately to be a nun. In the flush of religiosity attending her First Communion, she pictured herself in a sweeping black habit like the sisters who taught at her strict elementary school. Actually, I just made that last part up. Kelly was a kid after Vatican II, so the nuns probably wore jeans with holes at the knees and chain-smoked in the teachers’ lounge. I’ll have to ask her sometime. But the Sound of Music image makes for a better story.

I didn’t grow up Catholic, or any other religion for that matter. My dad was an angry atheist who considered religion a crutch for people who were too stupid to know any better. My mom was considerably more charitable but no more interested in organized religion than she was in volunteering for a Stalinist gulag. So it’s hard to explain why I was always drawn inexorably toward religion and religious people.

As a child, I looked forward to spending a Saturday night at my friend Gretchen’s house not only for the thrill of staying up past midnight but also because, no matter what time we nodded off, we had to wake up early on Sunday to attend services at her downtown Lutheran church. I loved dressing up in different clothes on Sunday, sneaking multiple donuts during the coffee klatch, and learning Bible stories on flannel board. This innate religiosity followed me through childhood. Even when I was away from home for two weeks each summer at Girl Scout camp, I’d attend both the Saturday evening Catholic Mass and the Sunday morning Protestant worship. At home, I talked several times to the friendly, guitar-playing Reform Jewish rabbi at my friend Sara’s synagogue. At ten, it seemed a good idea to keep all my options open.

But for twenty-five years now I’ve been a Christian, having sealed the deal with Jesus at a snowy winter youth group retreat during my freshman year of high school. In tears, freezing my ass off on a rock, I stared up at the stars and talked out loud to God like a crazy person. A peace washed over me when I knew God had marked me as his crazy person. That was it. I was no longer an outsider looking in on God’s family; I had a place at the table. I just didn’t know then that it would be impossible to maintain the same passion for God I felt at that singular moment.

I feel little romance for religion anymore. I don’t yearn for quiet time alone with Jesus or think about him every hour. These days, Jesus and I are like old marrieds—sometimes I’m a nag, and sometimes he is emotionally distant. Maybe the extremes I’m contemplating with a year of bizarre faith practices are the spiritual equivalent of greeting Jesus at the door wrapped only in cellophane. I’m trying to pop a little zing back into our relationship.

I should backtrack and explain. I am about to embark on an adventure. At the suggestion of some publisher friends, I am conducting a year-long experiment into reading the spiritual classics. Although reading was the extent of their original idea, I immediately upped the ante to include a corresponding monthly spiritual practice to supplement the reading. I guess I am an overachiever.

But which practices? And which spiritual classics? Everyone, it seems, has an opinion. My girlfriend Donna tells me that she absolutely will not be my friend anymore if I don’t spend at least one month reading Augustine. Since she’s Catholic, she pronounces this August-eeen, and since she’s the brainy by-product of about a kajillion years of Catholic education, she has strong opinions about his books. “Read The Confessions!” she exclaims. “No, read City of God! That’s a really good one, and it’s so neglected.”

I’m not that interested in City of God, preferring more personal tales I can relate to. I decide to start with Thérèse of Lisieux, having bypassed Augustine in the hopes that Donna was speaking in the passion of the moment and will still be my friend even if I ignore the guy from Hippo. I spend much of January reading Thérèse’s memoir, The Story of a Soul. The nineteenth-century French saint Thérèse is famous for bringing saintly wisdom down to the level of the hoi polloi, for calling herself the least of the saints—just an uncultivated “Little Flower” among all of God’s gorgeous roses. I figure I can relate.

It doesn’t go quite as planned, however. Instead of being the perfect kickoff to my year of trying to be a saint, the book makes me want to strangle the Little Flower. I’m puzzled by why so many people love Thérèse. In her memoir she calls herself “very expansive,” which is one of the great understatements of hagiography. In our day we might use different words: drama queen. Thérèse decided at an early age that she was going to be a nun, and nothing would deter her. She was so bound for holiness that she went over her priest’s head to the bishop to get permission to enter the convent in her early teens. When both the priest and the bishop failed to comply with her wishes, she actually went all the way up the chain of command to the pope himself and charmed his socks off in a personal audience. Actually, do popes wear socks? I do not know.

Don’t call me a saint.

I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.

—DOROTHY DAY

At any rate, the pope waived the age requirement for Thérèse so she could get her way and be the first in her class to join a convent. In the end, it might have been a good thing too, because Thérèse died in her early twenties of some appropriately nineteenth-century disease like consumption. But at least she had fulfilled her convent fantasy before she started wasting away in her cell. The book she left behind has inspired millions with its central idea that ordinary people can become “saints” too, wherever they are. I’m determined that this idea, at least, is something positive I will take away from Thérèse, even though I find her manipulative behavior annoying and have made a poor job of reading her book.

It’s helpful that Thérèse left behind some instructions about DIY sainthood for ordinary people, because in my own quest for sainthood, I’m not planning to join a convent, wheedle the pope, or contract tuberculosis. In fact, I start keeping a list of extremes to which I will not go:

I will not climb to the top of a pole and live there. Simeon the Stylite did this for thirty-seven years, actually strapping himself to the pole so he wouldn’t topple over when he fell asleep. I have zero interest in doing this. My bed is just fine.

I will not allow myself to be devoured by lions, like the early Christian martyr Felicitas. To be on the safe side, I will avoid all large arenas for the year. Also zoos.

I refuse to pluck out my own eyes for God. Legend has it that St. Lucia did this, then put her eyes on a plate and gave them to the fiancé she had

Dear Johned in order to pursue a life with God. So not happening here.

I will not strip naked and parade in the town square. St. Francis did this, but that was in Europe, where they also have nude beaches.

But if the opportunity arises, I will remain open to the following:

Magically bilocating. St. Drogo was allegedly able to achieve this, appearing in two places at once. This was not such a boon for others, however, as the afflicted Drogo is considered the Patron Saint of Unattractive People. Still, bilocation would be an enviable superpower in the harried twenty-first century. Sign me up.

Hanging out my shingle as a miracle worker, free of charge. Who wouldn’t want a miracle nowadays?

Although miracle working sounds exciting, I think that my spiritual practices will be more tried-and-true—like, say, prayer. I’m lousy at it and could use a whole new prayer MO. In lieu of fancy powers like bilocation, I’d be thrilled just to feel like God was accepting my calls.

I also plan a month to focus on reading the Bible, which is hardly going to win an extreme spirituality competition. But these tamer practices fit well with family considerations. I don’t want my year of radical spirituality to be a hardship on my loved ones, though some amount of sacrifice on their part is inevitable. At least, this is what I try to tell my husband, Phil, when we are lying in bed one night in January and I outline the year for him.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood