- Home

- Jana Reiss

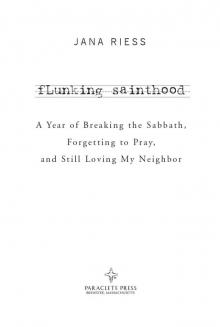

Flunking Sainthood Page 8

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 8

I am simply not getting along with Centering Prayer. What surprises me about my abject failure is that it’s not because I’m uncomfortable with silence. I’m a veteran of a number of silent retreats; I love being free of small talk, able to dream my own dreams. What little religious upbringing I had as a kid happened when my mom started taking us to Quaker Meeting when I was nine years old. (I think she figured that it was dangerous to grow up with absolutely no exposure to religion. If we didn’t have organized religion as children, what would we rebel against later?) Although silence at Meeting was as hard for me as it would be for any garrulous fifth grader, I secretly looked forward to the long hour of tranquility interrupted occasionally by the sound of the growling stomachs of those who’d unwisely skipped breakfast. And as an adult, since I’m an editor and writer, some amount of silence is a necessary—and pleasurable—part of my work.

So if it’s not the expectation of silence that’s the problem for me, what’s the trouble here? I think it’s the expectation that I’ll actually (not) pray, (not) listen, and (not) think during this time. As Bourgeault puts it, there is silence and then there is silence. It’s great to take a walk in the woods, but if your head is swimming with activity and worries then the silence is only external. She distinguishes between free silence, like the lovely hall-pass silence I find on retreat, and intentional silence, which is about training the promiscuous, free-floating mind and “almost always feels like work.” (You think?) The problem, as the Buddhists have long identified, is that when our monkey mind jumps from tree limb to tree limb, it brings the rest of the monkey along for the ride.

Each day I conclude that Centering Prayer can wait until later . . . except that “later” doesn’t exactly arrive anytime that day, or the next. Before I know it, I haven’t attempted to sit down for Centering Prayer in five days.

Even if you did nothing in your meditation but bring your heart back, and place it again in our Lord’s presence, though it went away again every time you brought it back, your hour would be very well employed.

—FRANCIS DE SALES

“The only thing wrong you can do in this prayer is to get up and walk out,” wrote Father Keating. I think he meant this to be helpful advice—hey, kids, you’re a success so long as you don’t give up! It’s like how nowadays at children’s events they get a trophy for just showing up at YMCA soccer or participating on a team. My daughter even got a “roller skating party” badge for her Girl Scout vest. In my day we’d have had to lash a tent together with dental floss if we wanted a badge.

But I would have been very proud of my tent. I don’t think that all the grace-filled badges and trophies that kids receive nowadays mean much to them, since they are keenly aware that they didn’t do anything to deserve it. So it is with me and Centering Prayer—Keating and Bourgeault can tell me again and again that I’m good enough and smart enough, but I’m the one inhabiting this particular monkey mind, and I’m the one who knows that I can’t cut it.

And so I quit. Just like that. Although I’ve failed to varying degrees at the five spiritual practices I’ve tried so far this year, I’ve never stopped cold turkey before. I am exhausted by the artificiality of trying to pray this way. I despise its formality and coldness.

I also despise myself, because contemplative prayer is about to join a long list of prayer methods I’ve already tried and failed. There were the slim, discreetly flowered prayer journals I kept in my purse in high school and part of college, when as a relatively new Christian I recorded my prayers for my own and other people’s problems. Mostly my own. Then there was the down-on-my-knees phase, when I attempted to pray every morning and evening in what I thought must be the holiest posture ever devised—holy because it was so uncomfortable that it was difficult to think about anything besides my sore knees.

These were followed years later by the prayer-walking phase, when I would strap baby Jerusha into a stroller and try to incorporate prayer into my daily walks. However, I kept getting distracted by the weather, thoughts about work, anxieties about child rearing, and willing myself to remember that tomorrow was trash day. This was followed by a much longer phase where I prayed haphazardly and without much forethought—which is where I still am most days. Apart from reciting the Lord’s Prayer with Jerusha at bedtime, my prayers are ad hoc and freeform, arising out of necessity for the people I love. The only thing I can be proud of in my prayer life is that when I promise to pray for someone, I actually do it.

Insights from two other people help me let go of Centering Prayer and stop beating myself up. First, I consult a writer acquaintance, Claudia, about my failures. She’s a prayer warrior and the author of a terrific book on Saint Teresa of Avila (not to be confused with Thérèse of Lisieux, who, as I mentioned in the opening chapter, was a first-class diva). When I confess to Claudia my complete inadequacies in Centering Prayer, she asks a simple question: why am I doing this?

That’s a very good question. The short answer, of course, is “for the book about reading and practicing spiritual classics,” but that doesn’t explain why I agreed to the whole memoir experiment in the first place. The real reason is that underneath all my cynicism, I felt hungry for God. I had hoped that Centering Prayer would be like getting my car battery jump-started on an icy day, and everything would suddenly roar back into life. But my spiritual battery remains incommunicado.

So Claudia lays this lovely paraphrase on me from St. Teresa:

Place yourself in the presence of Christ.

Don’t wear yourself out thinking.

Simply speak with your Beloved.

Delight in him.

Lay your needs at his feet.

Acknowledge that he doesn’t have to allow you in his presence.

(But he does!)

There is a time for thinking,

And a time for being.

Be.

With him.

Teresa, one of the great mystics of the Christian church, has given me a gold star just for trying! Claudia has made my day.

I also get a nod of comfort from my colleague Vinita, who is something of an expert in the spiritual disciplines and actually leads retreats on lectio divina, which I sheepishly confess to having already flunked a couple of months ago. “And now I’m a Centering Prayer dropout,” I admit.

She cocks an eyebrow and considers me for a moment across the breakfast table before weighing in with her raspy alto voice. I’ve always loved Vinita’s speaking voice, which has an unexpected Southern slowness for someone who actually grew up in Kansas. I hope she’s not about to use it to bust my chops.

“You know, in other world religions, this kind of deep prayer and meditation is not something a person would undertake without a teacher,” she says. I exhale. She is offering me a face-saving theological out. “That’s true in Sufism, Hasidic Judaism, and other traditions. And for Christian Centering Prayer, Keating would teach the method and reasons for it at retreats, to groups. It’s just not the kind of practice anyone should try alone,” she concludes.

So I say good-bye to Centering Prayer. Maybe we’ll be friends later in life, when I’ve grown up enough to calm my mind and the practice makes me less agitated rather than more. But I’m not holding my breath, either figuratively or literally.

THE JESUS PRAYER

A few years ago I interviewed an Orthodox Christian bookseller for an article I was writing, and we wound up having a wonderful conversation in which we discovered a shared love for several different authors. He said that I might like a book called The Philokalia, which I’d never heard of before. “That’s a book that’s gonna kick your ass,” he promised. It struck me as a sterling recommendation.

Now, casting about for a replacement prayer practice, I pick up The Philokalia—which at first glance seems to be a kind of greatest hits of the top monks of Orthodox Christianity. I want to learn what they have to say about the Jesus Prayer, one of the most simple and elegant prayers I’ve ever seen: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God

, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

That’s it, the whole enchilada. Four wee clauses packed with gospel truths: Christ’s lordship, his relationship to God, our need for forgiveness, our propensity to sin. It’s a prayer that Christians have been saying since about the fourth century. It’s a prayer I might even have a chance of living out.

But right away The Philokalia starts kicking my ass in a wholly different way than the bookseller probably intended. The Jesus Prayer is everywhere and nowhere in its four hundred pages, which are typeset in a font so small I think that there must be no Orthodox Christians over the age of forty-five. The book is a rummage sale of spiritual instruction: we’ve got aphorisms, we’ve got stories, we’ve got advice for future monks. I try to skip ahead to some of the texts on prayer—I’ve only got two weeks left in June now that I’ve screwed up Centering Prayer, so time is of the essence—but it’s not all that obvious where these texts are located. The ones with prayer in the title are way over my head since I’ve been to precisely one Orthodox service in my life, and my chief memory is that I spent it wondering if we would ever sit down. (We didn’t. There weren’t even chairs at the church.)

I should have suspected that people who can stand up for hours in their religious services are tougher than I am. So maybe I shouldn’t be surprised that when I do find the lowdown about the Jesus Prayer in a section called “Directions to Hesychasts,” it sounds more complicated than merely repeating twelve magic words over and over. (Hesychast, by the way, is not a dread disease, which is what it sounds like, but someone engaged in a form of mystical prayer. So now you know.) The Fathers actually break down the Jesus Prayer phrase by phrase and tell monks what they’re supposed to be learning and thinking at each stage. Not surprisingly, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God,” is designed to lead us back to Jesus Christ himself. Check. “Have mercy on me” turns the tables and invites self-scrutiny, “since he [the praying sinner] cannot as yet pray about himself.” Okay, struggling with prayer does sound like me. Check. But then the praying person is supposed to jump into spiritual hyperdrive by gaining “the experience of perfect love.”

Let the Jesus prayer cleave to your breath—and in a few days you will see it in practice.

—Hesychius, quoted in “Directions to Hesychasts” 22,

The Philokalia

Hang on. By word twelve I’m supposed to experience perfect love? It seems a lot to ask.

So while on the surface I’m not fighting with the Jesus Prayer to the same degree I battled with Centering Prayer, apparently it’s not enough to say it fifty times a day in my head, which is the modest goal I’ve set for myself. I sprinkle these recitations throughout the day rather than squeeze them in to a single session, and I like the feeling of remembering the Prayer when I am grateful, frustrated, or catch myself judging someone else. I honestly think it is helping me to remember Christ’s love throughout the day. I especially love a suggestion I read in a secondary source: that when we recite the first part of the prayer, we should inhale (“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God”), and then exhale through the rest (“have mercy on me, a sinner”). The idea is that we inhale divinity and then exhale our own sin. I enjoy imagining myself as a tree in reverse: taking in the good stuff and blowing out the bad.

But am I feeling perfect love? Not so much.

As I read on in The Philokalia I discover that some of the monks get a little anxious about letting neophytes sit in the driver’s seat of the Jesus Prayer without a bona fide license. They think these twelve words are so spiritually powerful that demons (who seem always at the ready in Orthodox Christianity) will take advantage of newbies who aren’t keeping their gaze fixed on Christ. Callistus says, for example, that the devil may try to trick me by “coloring the air to resemble light” or “producing flame-like forms.” However, it seems to me that such trippy manifestations of demonic activity would be a pretty obvious clue that something’s awry, so I choose to ignore him.

It also sounds like these cautions are intended for monks who feel themselves superior and imagine they’ve achieved a certain level of holiness. They’ve left humility behind. Not me, though. Not for nothing have I failed for six months continuously! If demons only attack those who think they’re experts at spirituality, then one of the benefits of finding out you pretty much suck is that it’s like spraying a demonic version of Off. When my assigned demons see that I’m hardly about to get cocky about the Jesus Prayer, they’ll yawn and wander off to play poker.

AT THE EMPATHY-FREE DENTIST

It’s during this time that I head off to the dentist chair for some minor work. I secretly call my practitioner the Asperger’s dentist, because he’s a fascinating example of someone who can be very good at his job—and talk endlessly about it whether you are interested or not—but be unburdened by human facilities such as understanding. He is almost wholly empathy-free.

I first cottoned on to that fact shortly after I’d had my miscarriage. I had canceled, and then rescheduled, some dental work for which I needed conscious sedation. He asked me why I had come back after canceling, and I responded that I’d had a miscarriage and was no longer pregnant, so I could have the anesthesia after all. I was admirably matter-of-fact when I laid this out, but in truth I was struggling not to cry.

Most men, upon hearing about a woman’s pregnancy loss, react in one of two ways. The sensitive ones will utter some version of “I’m sorry,” and you can see in their eyes that they truly are. The others become visibly uneasy and do their best to change the subject immediately or flee the room. Dr. Asperger had a completely different reaction: he started to laugh. He then launched into what he promised was a funny story about a woman who had had a miscarriage right there in his office.

Gesturing across the hall, where the allegedly hilarious incident had taken place, he announced that a patient had started bleeding out one day in the examining chair. “She was just, like, crying and stuff!” he said. “That lady was a mess! We had to call her doctor right then and there.”

He laughed some more as I tried to figure out what, exactly, he found so amusing. The dental assistant, obviously horrified by his lack of sensitivity, gestured madly to cue him to lay off.

Yes, gentle reader, I hear your cry. Why didn’t I just get up right then and walk out? This man was not created to deal with human patients. But he’s the only Cincinnati dentist in my insurance network who will knock me out cold for relatively minor procedures, which is a quality I value in a dentist. I’m stuck with him.

Things have improved since then, as I’ve adjusted to Dr. Asperger’s quirky ways and his tendency to take up ten minutes of a fifteen-minute appointment telling me about his board exams, the embryology of the human tooth, or his latest plans for renovating the office. The truth is that despite the complete absence of a bedside manner, he does excellent work.

Which is why I’m here today. Since I don’t need full sedation this time, I’m getting numb. “How you doing with the nitrous?” the assistant Trish asks solicitously, a little too loudly, as one might ask a nursing home patient how he is enjoying his lime Jell-O.

“It’s fantashtic, acshually,” I slur.

“Great!” she beams. “I’m so glad you’re enjoying it!” She is delighted to see me getting high. And for a while, this is how it goes in the dentist’s chair: I am loose and listening to my iPod, the dentist drills and does his thing, and my mind rambles off. Until . . . crap! That hurts! Something has gone wrong, and I am reduced to a quivering jellyfish, trying hard to be brave but desperately wanting it to be over. They numb me up again and wait a few more minutes.

“How’s that feel now, hon? Do you feel numb?” Trish asks, all concern. I am well enough to note the oxymoronic nature of this statement—if I’m numb, isn’t the point not to feel anything?—but not well enough to comment. I just open up my jaw and bear it. It’s like a nightmare.

And so I pray.

This, at last, is when I experience deeper success with the Jesus Prayer. I

need so desperately to get out of my own head that I just sit there, listening to Enya and saying lordjesuschristsonofGodhavemercyonmeasinner over and over again in my mind. It’s surprisingly calming and helpful. LordjesuschristsonofGodhavemercyonmeasinner. LordjesuschristsonofGodhavemercyonmeasinner.

“Prayer of the heart” occurs when the Prayer moves from merely mental repetition, forced along by your own effort, to an effortless and spontaneous self-repetition of the Prayer that emanates from the core of your being, your heart.

—FREDERICA MATHEWES-GREEN

A surprising thought occurs to me as I sit in that chair begging for Christ’s mercy: I’ve never actually forgiven Dr. Asperger for his social lapse after my miscarriage. I already know in my heart that he didn’t intend to be cruel, so why am I hanging on to this old injury? Whether he made the comment out of his own discomfort or out of complete ignorance about human psychology doesn’t matter. He was not trying to hurt me.

By reminding me I’m a sinner, the Jesus Prayer has allowed this scar to rise up gently before my consciousness, showing me that I’m hardly fit to judge my dentist when I am unkind to others, usually unintentionally but occasionally intentionally, all the time. The Jesus Prayer reminds me who I am in Christ—and just as important, who I’m not. I’m not God, with authority to judge others. I am a sinner, just like my dentist.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood