- Home

- Jana Reiss

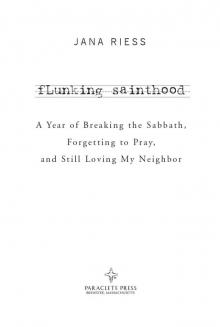

Flunking Sainthood Page 6

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 6

Except that it hasn’t quite worked out that way, because said child did not materialize. When I had that sense of Scripture being an answer to my prayer, other parts of our story simply did not occur to me, the parts where the dream is deferred or destroyed by unexpected infertility and miscarriage. Those parts of the story unfolded over time, amid sorrow and frustration and yes, even shame. It’s now years later, and I am left wondering whether I overspiritualized a coincidence. Was the psalm that we prayed at Gethsemani—not once but twice in the time I was there—merely an accident? Math is not on my side here. I mean, if the monks pray through the entire Psalter every two weeks and I was there for three and a half days, the odds aren’t really one in a million. In fact, they increase to about 50 in 150, odds that hardly require miraculous intervention.

This long-standing disappointment jostles itself to the forefront of my mind as I approach lectio divina. I try to stake down the temptation to regard any wisdom gained from merely opening the Bible and pointing to the first passage I see as divine. But what am I to think one day in April when, overwhelmed by responsibilities and tax anxieties, I open my threadbare print Bible straight to this passage from the Gospel?

Take heart, it is I; do not be afraid. (Mk. 6:50)

I feel immediately comforted. Somebody up there likes me. There’s someone in my corner. Coincidence, coincischmence! Yes, a skeptic would say that this particular fortune cookie had about a 99 percent chance of hitting its target; when am I not anxious and fearful about something? Yet I choose to believe that God sees and hears, that God loves me and does not want me to be consumed with worry. I don’t wish to inhabit an entirely rational world with no mystery. Lectio divina is going to be heart and head, not just head.

CONTEMPLATIO: THE ELUSIVE POT OF GOLD

Michael Casey makes the point in Sacred Reading that the four stages of lectio divina aren’t clearly delineated but function more like the shimmering hues of a rainbow, ebbing and flowing and sometimes overlapping. It’s a lovely image, but one thing is clear from his book: the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow is supposed to be contemplatio.

The word contemplatio is where we get “contemplation,” but the Latin implies far more than sitting around with our chins in our hands, thinking. It’s a course of action, moving forward from the text. The Bible is supposed to bear fruit in our lives; as I’m seeing in the Gospel of Mark, when the sower scatters his seed along the path, you want to be the “good seed” that sprouts sturdy plants, not the seed that gets choked by weeds, scorched by the sun, or felled by shallow roots.

The human qualities of the raw materials show through. Naivety, error, contradiction, even (as in the cursing Psalms) wickedness are not removed. The total result is not “the Word of God” in the sense that every passage in itself, gives impeccable science or history. It carries the Word of God.

—C. S. LEWIS

I get the concept, and I don’t want to be a bad seed. However, I’m not feeling much mystical union with the divine. At all. This is where it becomes very clear that, like with fasting in February, a month is not long enough to make any real headway with a new spiritual practice. Both Peterson and Casey talk about the years that are necessary to make tangible progress with lectio divina. Years! “Lifelong exposure to God’s word is more like a marathon than a sprint,” Casey cautions. I’m more interested in merely jogging once around the block.

But if I’m going to fail, I’d like to at least learn something in the process, and lectio divina has been surprisingly helpful in that regard. Primarily, it has shown me how I tend to skim the surface, not only of the Bible but of the Christian faith itself. Casey says that one “benefit that comes with the regular reading of the Bible is that we are brought face to face with the superficiality of our existing commitment. It is easy to believe that our lives are inspired by the Gospels if we keep the Gospels at a distance.” Confronting the Gospel of Mark each day has made me realize how demanding the Christian faith is, despite all my attempts to make light of it. Jesus’ disquieting temper tantrums illuminate my hard-heartedness; and the Bible, with its alternating impenetrability and bluntness, brings my own weaknesses into sharp relief.

I’ve now failed, to one degree or another, at three different spiritual practices, which is demoralizing. I’m disappointed in myself, but somehow I don’t think that God is. Even though reading the Gospel of Mark has shown me many of the ways I fall short, the Bible has been valuable in cracking the pedestal of “real” Christian faith for me. Perhaps I get so disturbed by Jesus’ anger and humanity because I am so afraid of those very shadows within myself. Maybe my determination to explore the Bible, warts and all, and to undertake the whole of the canon, exposes an underlying yearning for God to accept me, warts and all. I don’t want to put forward only my acceptable bits for prayer, don my Sunday best to inhabit a relationship with God. He gets to work with me in my sweat pants, as I kick up my feet on the couch. He gets to love me through my selfish, disciple-like desires to gain prestige or avoid suffering. Maybe he’ll love me by shouting at me to try harder, and this time I will listen.

Near the end of the month I have a minor epiphany. I’m walking Onyx and listening to Mark 13, in which Jesus speaks of the master returning suddenly in the night. His servants are supposed to stay on their toes while the master is gone so they can be prepared for his return, even though they don’t know precisely when that will happen. Onyx and I are well into the woods today, up in the winding trails of Ault Park while I listen to the Gospel. Just after Jesus admonishes his hearers to “keep watch” because they don’t know the day or hour of his coming, everything goes silent. There is no more sound from the audio Bible.

I suddenly become aware of how alone Onyx and I are, there in the trees with their new foliage, surrounded by the trill of birds and the high-pitched buzz of insects. A woodpecker thwacks away in the distance as Onyx lifts a leg to distribute largesse at his 437th tree. Keep watch, I think. Am I awake?

I wonder if the audio has included that moment of silence intentionally, to jolt listeners out of their comfort zones, if only for a moment. The thief in the night has come: a moment of sudden losses.

Then I realize I have a faulty headphone jack, which has dislodged during the hike. Only technical difficulties, then. Still, the experience of sudden disconnection from Jesus has been unsettling. I’m hardly at the stage where I’m experiencing mystical union with the divine, but I can honestly say I’ve been hanging on his every word.

5

May

nixing shoppertainment

The wonderful thing about simplicity is its ability to give us

contentment. Do you understand what a freedom this is? To live in

contentment means we can opt out of the status race and the

maddening pace that is its necessary partner. We can shout “No!”

to the insanity which chants, “More, more, more!” We can rest

contented in the gracious provision of God.

—RICHARD FOSTER

I’m not much of a shopper. My Midwestern frugality is so ingrained that I just can’t override certain price ceilings I have in my mind. A purse should cost no more than thirty dollars, for example, and a woman should only have one purse at a time or she will lose her keys and wallet. Or at least, I will lose my keys and wallet. I am entirely monogamous with purses; I am faithful to one at a time until the day my laptop computer has worn the straps off it, which usually takes about three years. Then I brave the stores to find a new workhorse purse, sometimes aided by a friend like my buddy Donna, the Augustine fan from chapter 1. She helped me shop for a new handbag a few years ago and was undaunted by my various rules. She actually seemed pleased at the prospect of a shopping challenge.

“It can’t cost more than thirty dollars,” I instructed. “It has to have long, sturdy straps, and be big enough to hold my laptop and at least one heavy hardback, but not be colossal enough to give me scoliosis. It has to be a solid color tha

t will go with everything. It can’t have been made by slave labor. Oh, and it has to have lots of little pockets inside.”

“Oooo-kay!” she said. An experienced shopper, she took charge, and within an hour had found me the perfect candidate at a Filene’s Basement in Manhattan. It was a splurge for me at $34.99, but it met all the requirements. We celebrated with cupcakes at Magnolia Bakery.

It was a marvelous day, being with Donna, but in general, I’m not a fan of shopping. The good news about this is that my May practice of not shopping should be a breeze. I already have a lifetime of stored memories of shoppertainment deprivation, and aside from a brief stint in junior high when I cared about details like designer labels, I’m not that fussed about fashion. What’s more, I’m married to the biggest cheapskate in America, whose car has 200,000 miles on it and who wears his shoes until the sole is hanging from the leather and I can glimpse his socks. Phil comes by this honestly; he was born to a long line of cheapskates. When we all get together at Thanksgiving and for summer holidays, we unconsciously indulge in a little game I call Competitive Frugality. Conversations go something like this:

“Hey, I like that shirt on you. Is that new?”

“Well, new to me. I got it for three bucks at Goodwill.”

“That’s great. Hey, check out my new jeans. I dug them out of the dumpster behind Goodwill.”

“Seriously? Score!”

I’m exaggerating, but not by much. The whole ethos of our family encourages thrift and making do with less. I own twelve pairs of shoes, which for an American female is downright ascetic. Not shopping is going to be so easy.

THINKING BIG

This month I’m going to abstain from all shopping except for our weekly groceries. Anything that’s not immediately necessary—anything that’s a want and not a need—will be put on hold. My first small test is on May 3, when I squeeze out the last remaining drop of foundation from my cosmetics tube. Going nearly a month without foundation is probably not what the saints meant when they talked about “dying to self,” but it’s a start. Makeup is not a need. I’m doing well so far with this spiritual practice.

Frugality is good if Liberality be join’d with it. The first is leaving off superfluous Expenses; the last bestowing them to the Benefit of others that need.

—WILLIAM PENN

I’m also going to avert my eyes from advertising. Since we have DVR, I’m accustomed to skipping over television commercials, but this month I’m trying to steer clear of print ads as well. Suddenly, they are everywhere: billboards on the Interstate, full-color spreads in the magazines I read, pop-up annoyances on websites. It’s like playing Whac-A-Mole every day to avoid them, but I’m succeeding enough that I start to feel proud of myself.

I should know by now, in my fifth month of spiritual experimentation, that the moment I start patting myself on the back is the precise moment I begin to fail. My confidence erodes when I commence reading Richard Foster, my spiritual guru for the month. Apparently, rejecting consumer culture is just the tip of the iceberg. What I need to aim for is simplicity in every area of my life. In Freedom of Simplicity: Finding Harmony in a Complex World, Foster encourages me to look beyond the practice of rejecting consumer culture to get to the root of what simplicity means for Christians. Which is anything but simple. “There simply are no easy answers to the tough questions of how we are to relate with integrity to the modern world,” Foster writes. Terrific.

But there are clues: I need to be hyperaware of all the ways I seek status and approval from other people. For many people, that’s shopping, but it’s no real feather in my cap that shopping’s just not my thing. Even though I’m not defining my worth by the label on my jeans, I have my own vanity Waterloos. Like being petted with praise when I speak at a conference and people applaud my ideas, my brain, my verbal quickness, my humor. I just eat that shit up. And yes, I say “shit” here because that’s what the potty-mouthed apostle Paul calls anything that we feel inordinately proud of but ultimately doesn’t point to God. The word he uses in Philippians 3 is skubula, which is not the most respectable way Paul could have phrased it. The Greek of his day had its own euphemisms, polite terms like poop and caca. Paul could have chosen any of those words, but he didn’t, presumably because he wanted to call attention to the foulness of all our status-seeking. We are sinners, full of shit. I most of all. There is excrement in me.

Foster wants me to analyze my whole life, not just my materialism, for anything that’s pulling me away from a simple life with God. This requires keeping a log of all my daily activities. And I do mean all of them. If I spend twenty minutes watching YouTube videos of cats who’ve been trained to flush the toilet, something my ten-year-old finds inordinately entertaining, I’m supposed to write that down. If I clock an hour looking at catalogs—wait, I’m not allowed to do that this month—I have to record that too. After I’ve spilled everything into the list, I’m to rank the items into four categories:

• Absolutely essential (1)

• Important but not essential (2)

• Helpful but not necessary (3)

• Trivial (4)

I feel dorky doing this exercise throughout early May. It reminds me of the “mission statements” that a lot of my friends wanted to write in the 1990s, inspired by Steven R. Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. I basically failed at the whole mission statement thing, but I am going to give this list a genuine Girl Scout try.

I’m supposed to wait until the end of the month to add them all up, but I’m too impatient and take stock after about a week. I’ve assembled quite a list. The next part is the kicker: “ruthlessly eliminate all of the last two categories and 20 percent of the first two.”

What! Everything from the last two categories? Is he serious?

Here’s what is in my bottom two categories: all the fun stuff. Like going to see Star Trek in the theater with my family, or watching the Reds lose again, or staying up too late to laugh with friends at book club. All that’s left when those frivolities disappear is the endless round of work tasks that wound up in the “essential” column: the final chapters I need to edit before I can transmit one of my author’s books into production, the edits I need to make on my own book before I submit it to my publisher, the conference paper I have to conjure out of thin air by next week. This new life doesn’t strike me as joyfully simple; it sounds dreary and austere. I get to go to work, and I get to floss my teeth. Blech.

OKAY, THINKING SMALLER NOW

This austerity doesn’t resemble the joyfully simple life I am craving. It also doesn’t sound much like a life Jesus would prescribe; after all, the guy’s inaugural miracle occurred at a party where he turned water into wine. Jesus was hardly a killjoy.

I stop obsessively writing down all my activities. As much as I’m loving the Foster book—the best thing I’ve read so far for this sainthood project—I’m going to give myself a pass on the puritanical self-scrutiny of every single minute of my days. Maybe years from now when I am some kind of Super Christian I will feel ready to embrace the kind of monastic life he recommends. And it is monastic. The Benedictines used to say that life should be ora et labora—work and prayer. That’s pretty much all that’s left to me after cutting out inessential activities. And I only ranked prayer as essential because I thought I should, not because it feels essential in the way that catching up on the last-ever episodes of Battlestar Galactica feels essential. I do have my priorities.

So I return to the original focus of not shopping and deal with the glaring problem of Mother’s Day. I kind of forgot about it until after May had already started, which is a problem because now I can’t buy a gift. My mother loves getting special presents, and since my bohemian brother rarely remembers to do anything, I feel the whole Mother’s Day burden on my shoulders. Do I skirt the letter of the law by telling my husband what to buy and having him place the order? Even I can see that’s cheating. Do I send a card and promise a gift on, say, June 1? That might

actually work.

I know what Brother Richard would say now: why am I trying to commodify the love and respect I feel for my mother by spending a fortune on flowers that will wilt, books she could check out of the library, and chocolate that will last approximately six minutes in her house? Mother’s Day is a celebration of love, not presents. And part of the whole joy of the day is knowing that I have the kind of mom who will completely understand that I can’t buy a gift right now because of some nutty book I’m researching. I call and explain. She is not just accepting but delighted, especially when I promise to come visit over Memorial Day weekend—the best substitute for a gift.

THE COMFORTABLE SPIRIT

A few years ago I took care of a friend after she had a face-lift, her fiftieth birthday present to herself. If I had ever harbored any interest in getting plastic surgery, that weekend with Margaret (not her real name) may well have cured it. The surgery itself was done on a Friday morning, and the clinic released her to my care in the early afternoon, after I helped her to get dressed and listened to the nurse’s instructions about pain medication. I couldn’t believe they were letting her go home in that condition. The parts of Margaret’s face that I could see around the bandages were already turning shades of saffron and indigo. As I drove the car gingerly to her house, she dozed in the passenger seat, then mumbled for me to pull over so she could throw up by the roadside.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood