- Home

- Jana Reiss

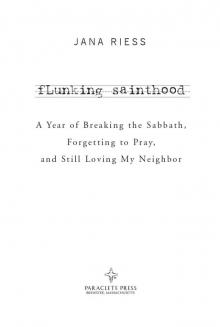

Flunking Sainthood Page 3

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 3

The reasons for this gender discrepancy are still unclear. Women’s drive to eat may be related to the hormone estrogen, to socialized patterns of emotion, or to a more primal evolutionary drive to consume every last Oreo while it is around, since women have always been the primary feeders of the young. Whatever the reason, it seems to make obesity more of a potential issue for women, and fasting more of a hurdle.

You’d never know that, though, from reading some of the heroics of the crazy medieval women saints, several centuries after the Desert Parents. These women’s fanaticism makes the Desert Mothers look positively domesticated. The most extreme saintly asceticism came in the Middle Ages, when the emaciated look was equated with greater holiness, especially for women. (It seems not much has changed in our culture’s equating thinness with discipline and righteousness.) Medieval literature speaks glowingly of how these female saints languished for Jesus while their bodies wasted away to nothing. Although women account for only 17.5 percent of all saints who were canonized or venerated between the years 1000 and 1700, they account for 29 percent of saints known for “extreme austerities” like outrageous fasts and sleep deprivation.

Women also dominate the category of food-related miracles; some of these bony devotees spontaneously lactated and nursed without ever giving birth, while others reportedly emulated Jesus’ miracle of feeding the five thousand with just a few loaves and fish. What does this mean for us? It means that fasting for all Christians can sometimes go too far, and that women in particular might need to be careful. It’s a slippery slope. First you’re trying out a simple fast, and the next thing you know you’re like Hedwig of Silesia, levitating at the mere sight of the Eucharist, your gaunt body rising with ecstasy at the thought of a single morsel.

I reflect on all this fanaticism as I fast here in the twenty-first century, when tabloids are filled with news about which celebrity has shed her pregnancy pounds, and women’s magazines, in bizarrely bipolar fashion, sport luscious layer cakes on the cover while promising surefire diet techniques in the pages within. It’s a sad commentary on our weight-obsessed culture that we don’t see the value of a fast for much except health and beauty. I critique the sentiment, chastising vanity and channeling my inner feminist to scourge the sexism of the diet culture, even while harboring a secret hope that maybe, in fact, I will drop a few pounds. Then I feel rotten about how worldly and vain I am, and determine not to diet, not to cast off a single ounce.

And yet it happens, even as I am eating Girl Scout cookies almost every night after dinner. I can hardly understand it, yet it is real, a bona fide postmodern miracle. The anti-manna. I am losing weight even while eating whatever the hell I want to for thirteen out of every twenty-four hours. Fasting is fabulous. I need to write a best-selling diet book.

“Wanna see something freaky?” I ask my husband and daughter, who are perched at the kitchen counter eating the supper I’ve prepared for them as I wait for the sun to go down. It’s three weeks into the February fast. They confess that yes, they would love to see something freaky. And so I pull my pants down, right there in the kitchen, without even bothering to unbutton them. They slide right off. Jerusha is delighted by the transgressiveness of this unexpected act, and starts to laugh. Phil is startled and a little bit worried as he laughs along with her.

“Are you sure you’re eating enough?” he asks.

“Yes, I think so,” I reassure him. “It’s not as dramatic as it seems. These are already my biggest jeans.” But in my mind I am already thinking about The Box in the basement, the one that holds my B.J. jeans (Before Jerusha). I wonder if I could ever fit into those again?

I am simultaneously proud and ashamed of myself. In her excellent book on fasting, Lynne Baab talks about the hidden dangers of fasting in a diet culture, when we are fasting for some other reason than simply to grow closer to God. Some people, she argues, should never fast from food, and it’s not just the usual suspects—pregnant or nursing moms, diabetics, the elderly, the infirm. She also exempts anyone who has ever struggled with an eating disorder, and admonishes yoyo dieters who might be tempted to try crazy fasts for anything but spiritual purposes. I am particularly struck by what she says about the motives for fasting, which come down to a simple saying of Jesus: no one can serve two masters. If we’re fasting for the secret purpose of weight loss, we aren’t doing it with the singleness of heart that the Bible encourages.

As much as I get it, it’s another thing to live it: I remain secretly pleased by the less matronly figure I spy in the mirror.

SO I’M FASTING . . . WHY, EXACTLY?

If I’m not fasting for weight loss or self-improvement, why am I doing this? Some clarity comes when I read Scot McKnight’s book Fasting, which challenges me to avoid fasting only in order to squeeze something spectacular out of God. McKnight wants Christians to move away from a spiritually immature idea of fasting (that is, to manipulate God into answering our prayers) to a more mature notion of focusing attention on God and letting worldly things fall away. McKnight objects to the whole “if A, then B” paradigm of fasting, calling Christians not to practice “instrumental fasting”—fasting with the idea of God as Santa Claus who will reward us if we’re really, really good and don’t eat all the cookies.

Fasting is not the means by which we are somehow turned into Aladdin and God is turned into our compliant genie, sent to grant our every wish. We must not think that by not eating we can have God eating out of our hand.

—LYNNE BAAB

I cheer for McKnight’s argument but can’t rise to that level of maturity. Maybe it’s just too many years spent in a conservative church that at least implicitly teaches that when we fast, we can count on loads of good stuff coming our way: physical healings, answers to spiritual questions, divine guidance on relationships, the works.

What’s more, I’ve experienced enough of those happy results myself that I can’t just blithely dismiss them as a false use of fasting. Once, in my congregation, all of us fasted and prayed for a little boy who had been in a serious car accident. He recovered completely. What can I say? Yes, he was getting the best medical care; yes, he had a tremendously supportive family; and yes, maybe he would have pulled through no matter what. It’s very possible that his recovery had nothing to do with the fact that two hundred people gave up food and drink so they could more completely concentrate their prayers for his recovery. But somehow, that explanation does not resonate with the wholly unscientific feeling I got about the affair. I felt a spiritual confirmation of how much God loved that kid, and that sense was somehow wrapped up in the greater closeness we all felt to God because of the fast.

So although I cringe when I hear simplistic theology that suggests that God will “honor” a fast by waving his fairy wand and granting whatever we ask just because we managed to spend a whole day without opening the refrigerator door, I admit there’s also a part of me that wants my fasting to be precisely that effective and tangible. I wish that fasting were a viable means of supersizing my prayers, of making them jump the queue somehow so that they’d be shouted directly into God’s right ear. It’s ridiculous, and it’s selfish, but I acknowledge the superstition and the selfishness even as that secret part of me wants to regard fasting as an efficacious form of magic. And so throughout the month I am praying: praying for a family member who’s having a rough time, praying for the wife of a colleague who’s been in a devastating car accident. Every time I feel a hunger pang—which is every few minutes most days—I send up a prayer.

A brother said to an old man: “There are two brothers. One of them stays in his cell quietly, fasting for six days at a time, and imposing on himself a good deal of discipline, and the other serves the sick. Which one of them is more acceptable to God?” The old man replied: “Even if the brother who fasts six days were to hang himself up by the nose, he could not equal the one who serves the sick.”

—SAYINGS OF THE DESERT FATHERS

MISERY LOVES COMPANY

A

s I fast, I’ve been open about what I’m doing, whether it’s explaining to colleagues why I’m eyeing their sandwiches greedily during a “working lunch” or announcing what I’ll eat when I get to break my fast. After a couple of weeks of this, as I continue my research into what the Bible and church tradition have to say about fasting, I come across this New Testament passage that I’ve conveniently forgotten:

And whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward. But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you. (Matt. 6:16–18)

Well, damn. I’m barely halfway into this experiment and already I’m doing it wrong. Apparently the fast is supposed to be sub-rosa, a little secret between me and Jesus. I guess maybe this means I shouldn’t have posted as my Facebook status things like, “I am about to break the fast!” or, “I have three long minutes until sunset.” I might as well set up a soapbox in Pharisee Square and shout to the world how I thank God for being so righteous.

The thing is, though, that I can honestly say I never intended to call attention to my fast to earn frequent righteousness miles. It’s more out of loneliness, actually. This whole month the most spiritually helpful day of fasting was actually the very first, and that was because it was an ordinary Fast Sunday at my church, when everyone else was fasting too. On the first Sunday of the month in my denomination, everybody fasts who is physically able to do so, and we donate the money we would have spent on food to help the poor. On that Sunday, I felt a solidarity with my fellow Christians that I haven’t felt on any other day this month. Overall, it’s been a very isolated journey.

It is not good for people to fast alone. I’m craving community almost as much as food. In the Orthodox Christian tradition, where literally half the year is made up of various sorts of fasts, the community factor is a given. “One can be damned alone, but saved only with others,” goes a Russian Orthodox saying. Apparently it takes a village to raise a Christian.

As I near the end of February, I think about the dichotomy of what I clandestinely wanted from fasting—community—and what I chose to read this month: the Desert Parents, who are famous for renouncing community. Duh. The Desert Parents looked at fasting as the linchpin in a series of austere spiritual practices, which included sleeping on the ground (mentioned specifically by the Desert Mother Synclectica as beneficial) and celibacy. I don’t intend to try either, nor am I interested in turning my back on the world. I like living in the world. I enjoy food and sex. And unlike the Desert folks, I’d be unhappy in a solitary life. I want my fasting to be a great big food-free party with everyone I know, where we all go hungry together. It occurs to me that the choice of Ramadan as a practice to emulate—a choice that seemed arbitrary at first—likely stems from a hidden jealousy I feel for the community that’s created when a billion people around the world fast as one.

Although this month’s spiritual classic wasn’t always easy to relate to, it took reading the Desert Parents to realize that I don’t wish to be them. That’s good to know.

On my last night, I have to wait for twelve minutes after Phil and Jerusha have started eating before I’m allowed to pick up my knife and fork. This is it. I have made it. The fast is over.

Phil looks at me indulgently. “Don’t ever, ever do this again,” he pleads.

But I am not so sure. True, not one of the “things” I have been praying for has happened—my friend’s wife remains in a coma, my family member is still struggling—and Jesus as Fairy Godmother has not officially recognized any sacrifice on my part. I’m no further on the journey to spiritual enlightenment or humility than I was twenty-eight days ago, which is discouraging. Yet physically, the fasting is so much easier than it was then. My body has adjusted to the new sleep schedule and to the absence of food during the day. There are still constant hunger pangs, but the feelings of weakness and bone-numbing cold that plagued me in the beginning have disappeared. Instead there are occasional glimmers of quiet elation and tranquility. I am more astonished by this than anyone.

“We’ll see,” I tell Phil. “Can you pass the chicken?”

3

March

meeting Jesus in the kitchen . . . or not

We can do little things for God; I turn the cake that is frying on

the pan for love of him, and that done, if there is nothing else to

call me, I prostrate myself in worship before him, who has given

me grace to work; afterwards I rise happier than a king.

—BROTHER LAWRENCE

At first, I don’t much like Brother Lawrence, the seventeenth-century French monk that everyone keeps telling me I need to read this month, as I attempt to infuse daily tasks with a sense of God’s presence. Brother Lawrence is famous as a kind of cooking saint: assigned to kitchen duty for fifteen years in a monastery, he allowed his deep love for God to suffuse every meal he created, every pot he scrubbed.

I try to like him. It’s just that he’s so sanctimonious.

Part of my initial disconnect is the cultural divide that separates us. The book compiled from Brother Lawrence’s letters and conversations, The Practice of the Presence of God, is one of those spiritual classics that thousands of people have read and been transformed by. But its language and tone are off-putting: I hate it that Brother Lawrence sometimes refers to himself in the third person. That may have been a post-Renaissance man’s best shot at appearing humble, but nowadays it comes across as anything but. I’m also bothered by the relentless cheer of Brother Lawrence’s opening pages. I mean, being European in the 1600s was not exactly a cocktail party: there were religious wars, beheadings, and smallpox outbreaks, all compounded by unfriendly realities like an absence of central heating and cable TV. Add to that some of the particular unpleasantness of monastic life: the 3 AM self-flagellations, the throwback medieval spoils system, the often-unreasonable abbots who were wealthy second sons with no special call to the brotherhood. I’ve watched every episode of Cadfael. I know how it was. But you’d never intuit any of that if you only had Brother Lawrence to rely upon, because the man was infuriatingly jolly. When he joined the monastery he’d been given numerous responsibilities, including all the icky chores that more established monks reserved specifically for greenies. But he never whined. Brother Lawrence’s biographer wrote:

Although his superiors assigned Lawrence to the most abject duties, he never let any complaint escape his lips. On the contrary, the grace that refuses to be disheartened by harshness and severity always sustained him in the most unpleasant and annoying assignments. Whatever repugnance he may have felt from his nature, he nevertheless accepted his assignments with pleasure, esteeming himself to be too happy either to suffer or to be humiliated by following the example of the Savior.

What a sycophant.

But I am going to have to delve deeper than my initial impressions, because Brother Lawrence apparently holds the keys to mindfulness in the Christian tradition. Apart from me, everybody adores him. Here’s what Hannah Whitall Smith, a Quaker, said in the nineteenth century about Brother Lawrence’s spiritual approach: “It fits into the lives of all human beings, let them be rich or poor, learned or unlearned, wise or simple. The woman at her wash-tub, or the stonebreaker on the road, can carry on the ‘practice’ here taught with as much ease and as much assurance of success as the priest at his altar or the missionary in his field of work.” This sounds promising.

It occurs to me that it’s no coincidence that Brother Lawrence’s writing, neglected by French Catholics after his death, was subsequently championed by English and American radical Protestants like Hannah Smith: his DIY spirituality coordinated precisely with their worldview. No intermediary was necessary. Just step right in, folks! Scrub those dishes, and presto change-o, you’re that much closer

to God. Anyone can do it, anywhere, even in the most profane of spaces. You don’t need a priest, a scribe, or a Eucharist. You just need a cutting board and a cleaver, and suddenly you’re flying down the Spirituality Express.

RINSE, LATHER, REPEAT

For all my early doubts about Brother Lawrence, cooking does seem a marvelous way into spirituality, especially just after my month of fasting and self-denial. I enjoy cooking, although like most people I sometimes get tired of it. Maybe even Brother Lawrence in his less holy moments would have preferred to book a table at a Parisian bistro rather than knead the bread dough one more time. But although I too often have to cook hurriedly, there is something deeply healing about taking whole fresh ingredients that are inedible in their original state and transforming them into something delicious and nutritious. When I am anxious, the act of cooking or baking can settle me into a rhythm of tranquility.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood