- Home

- Jana Reiss

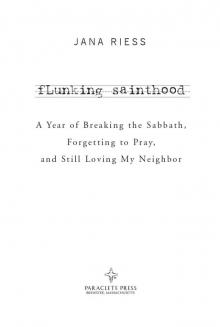

Flunking Sainthood Page 2

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 2

“What I’m thinking,” I announce, “is that there will be a month where I fast, and a month where I try not to spend money, and a month where I observe an Orthodox Sabbath.” I can tell that he is listening, but in a halfhearted way as he attends to his Sudoku puzzle. I drop the bombshell.

“And then, of course, there has to be a month where I don’t have any sex,” I explain matter-of-factly. “That will be in November.”

“Okay. Uh huh.” There is a pause before his head snaps over to me with an alarmed expression. “No, wait, what did you say?”

“I said that in order for this to be authentic, there has to be a month where I give up sex. I mean, look at all the saints. Most of them were celibate their whole adult lives. Abstaining for a month is the least I can do. I think I can make it, so long as I have chocolate.”

I’d rather laugh with the sinners than cry with the saints; the sinners are much more fun.

—BILLY JOEL

“But . . . but . . . ” I definitely have his full attention now. “Are you serious?”

It would be great fun to see how long I can keep this going, but eventually I put him out of his misery and admit that I’m bluffing. He is immensely relieved, which makes me realize I’ve scored one point at least: anything else I subject the poor man to this year will seem like small potatoes compared to the forced celibacy I could have inflicted upon him. I will remind him of this fact should his enthusiasm for my project ever flag.

Even though I don’t quite know where this project is taking me or what this year will bring, I’m glad that I’ve decided to bring spirituality down to earth by trying to actually live it and not just read about it. In her book Mudhouse Sabbath, Lauren Winner points out a scene in Exodus 24 where the Israelites get the Ten Commandments and promise to obey God. The odd part of the story is the word order of their response: “All that you have said we will do and hear.” Wait a minute, we think. Shouldn’t that be the other way around? How can we do what God commands until we’ve heard it first? Some biblical scholars say this is just a scribal error, and it’s certainly possible that we’re all reading too much into this particular bout of biblical dyslexia. But I prefer the rabbinic explanation Lauren gives: some rabbis have taught that we can’t really hear what God is saying, or let it sink into our souls and beings, until we have tried to do what God is saying. The practice precedes the belief, not the other way around. Interesting. It’s like what Abraham Joshua Heschel, a rabbi we’ll meet again in chapter 7, has to say about spiritual practice. Although he’s speaking here specifically of Jewishness, it’s applicable to spiritual practice for everyone:

A Jew is asked to take a leap of action rather than a leap of thought. He is asked to surpass his needs, to do more than he understands in order to understand more than he does. In carrying out the word of the Torah he is ushered into the presence of spiritual meaning. Through the ecstasy of deeds he learns to be certain of the hereness of God.

I’m not sure I’ll be feeling much of the “ecstasy of deeds,” but I do know there’s a common thread in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament of walking with God. Enoch and Noah (Gen. 5 and 6) were righteous because they walked with God, not because they believed the right things about God or passed an orthodoxy litmus test. (Just FYI, in the interest of full biblical disclosure: the Bible makes this observation about Noah’s righteousness before the guy gets totally wasted and curses one of his sons. After Vineyardgate, the Bible has no comment about Noah.) Walking with God comes up again in Deuteronomy 10, in the Exodus, and in Micah 6:8, one of my favorite Scriptures. To paraphrase, Micah says God has already shown us what is good: to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with God. I like that. This year is going to be about walking with God and taking a leap of faith with spiritual experiments.

And really, how hard could that be? I’m about to find out.

2

February

fasting in the desert

A fat stomach never breeds fine thoughts.

—ST. JEROME

5:57 PM. I’m seated in a straight-back wooden chair at a suburban Cracker Barrel, counting the minutes until the sun sets at 6:04 and I can break my fast. Say what you want about the Cracker Barrel, but when the chips are down, it’s the soul food of any self-respecting Midwesterner. You can keep your arugula and sashimi. Pass me the mashed potatoes.

“Could you please bring the biscuits before the meal? And some jam? And a glass of chocolate milk?” I congratulate myself on keeping the edge of desperation out of my voice.

“Sure thing, hon. Be right back,” promises the waitress as she dashes away. However, she doesn’t return for a full fifteen minutes. The place is jammed with customers, and the smell of their meatloaf overpowers my senses as I gesture unsuccessfully to recapture her attention. I busy myself with my iPhone and try not to notice each minute ticking past on the digital clock in its top right corner.

“I’m so sorry, hon. We got slammed all of a sudden,” the waitress apologizes as she shoves various items on the table. I smile her way but don’t speak because I’ve already crammed a biscuit in my mouth. I demolish the bread, the milk, and what passes for vegetables at the Cracker Barrel. Nothing has ever tasted so delicious.

I hate fasting. How am I going to make it through a month of this?

This month, for my first grand experiment, the plan is to read the Desert Fathers and Mothers about fasting and see what wisdom the ancient sages might have to offer me, a relative newbie to this ancient art. The Desert Parents were some of the first hermits of the Christian tradition. We call them “parents,” but that’s only in a spiritual sense; they were celibate monks and nuns of the third century onward who fled family life and the city so they could meet God out in the hinterlands. They lived simply, selling all their possessions, and they usually embraced solitude. Or at least, they tried to. Solitude was hard to come by, because some of the Desert Parents were like rock stars in their day. Ordinary folks had the annoying habit of knocking on their caves for marital advice, miraculous healings, or a nice pithy aphorism or two. And such intrusions were actually a good thing, because sometimes the groupies took the trouble to write down the Desert Parents’ teachings.

As ascetics, the Desert Mothers and Fathers had a great deal to say about fasting, and I’ll be reading those teachings this month. But the twist is that I am going to do the Christian fast like a Muslim during Ramadan. Although I like the Desert Parents in theory, I’m not keen to emulate their actual fasting practices, which included severe self-denial. Some didn’t eat or drink for days or even weeks on end. This seems to me like an engraved invitation for psychosis, so I’ll pass. I need a more moderate fasting practice that I can implement from day to day. I’ve always admired the annual Muslim tradition of fasting from sunup to sundown and wondered if I could do it. This is my chance to put it into practice. It seems far more sensible than outright starvation.

It’s no accident that fasting is going to be the first spiritual practice I attempt. I’d love to tell you that I plotted out my year in this way because I was so excited to fast that I simply couldn’t wait. But the real reason I wanted to do this discipline early in the year is because if you’re fasting from sunup to sundown, what better time to do this than in winter when the days are short? And at just twenty-eight days, February is the briefest month on the calendar.

I need to become vigilant about the times the sun rises and sets, so I begin my pre-February preparation by checking online for a sun calendar for Cincinnati. On the first day of the month, I plan to get up around six o’clock to have time for a huge breakfast before sunup. The days will get a little longer as the month wears on, which means I’ll have to get up earlier each morning and break the fast later each evening. But it’s all right; I feel ready. I can do this. Bring it on.

While you are young and healthy, fast, for old age

with its weakness will come. As long as you can,

lay up treasure, so that when you cannot, you w

ill be at peace.

—SYNCLECTICA

BOOT CAMP

It turns out that “bring it on” is not the most humble, spiritual phrase with which to begin a fast. Although I commence with the enthusiasm of a zealot, by the middle of the second day I’m hungry enough to call it quits and devour everything in the refrigerator.

In my church we fast once a month, but it’s always on a Sunday, which means I’m not expected to produce coherent thoughts or speeches, and I can usually accelerate the experience by taking a two-hour nap in the afternoon. Fasting on a weekday is a whole different kettle of fish. I feel fuzzy and unfocused as I answer e-mails and craft a report. The positive side of not taking an hour off for lunch is that I have more time to work, and am in fact itching for something like work to stop my brain from thinking about food. The downside is that it’s difficult to concentrate. I’m starting to curse one of the things I’ve always loved about our neighborhood—the proximity of great restaurants right around the corner. I can smell naan baking, and what I guess to be curry.

Time passes slowly, the clock as slothful as my own body. “I don’t know if I can do this,” I complain on day three to a Muslim friend who fasts like this every year. “I’m so hungry and tired all the time.” I sound whiny even to my own ears, and feel about six years old. And I can’t even think about the faith-related reasons I’m supposed to be fasting; I don’t feel any closer to God and haven’t experienced any of the Desert Parents’ promised fonts of spiritual wisdom. I’m just trying to get through each day without cheating on the fast or strangling someone. It seems a tall order.

“It will get better,” she promises. “It’s normal to feel exhausted at first. A lot of people take naps during the day if they can.”

No kidding. I feel like I’ve been given narcotics. I’m grateful to work from home, and start shifting my work schedule to accommodate an afternoon nap during my former lunch hour.

One area where fasting cramps my style is in my writing. I love to write at cafés, with a mug of hot chocolate, noise-canceling headphones, and two hours without the interruptions of editing or family life. But what’s the coffeehouse protocol for moochers? Could I go to the café, order something, and then stare at it like a wounded puppy for two hours? Or should I tell Tony, the friendly proprietor of the Coffee Emporium, that I am riding on the coattails of his Wi-Fi this month but have no intention to purchase anything for four weeks? Neither option sounds appealing, so I reconfigure my work life to write from home with only partial success. I feel vaguely housebound.

On day five, I hit my Waterloo. I have to commute into the office for meetings. Because I wake up late, I eat breakfast quickly, cramming shredded wheat cereal with blueberries into my mouth in a mad race against the colors in the sky. But by the end of my two-hour drive, I’m already hungry, and I have more than nine hours to go until sunset. It’s an awful day—the weather is appalling, I can’t silence my growling stomach, and I feel cold from head to toe. I wear my wool coat almost all day as I sit in meetings, musing on the truth of at least one thing I’ve read: fasting lowers a human being’s core body temperature. Hypothesis confirmed. I am now a science experiment.

Why did anyone ever imagine that there was anything spiritual about fasting? This is boot camp. It feels punitive and harsh.

The very next morning, though, brings a breakthrough. Before dawn, I meet my friend Jamie for a blowout breakfast at IHOP, indulging in an omelet with toast and hash browns. Even though I can’t finish the enormous omelet, I find that it’s enough to see me through the day. Miracles and wonders! Six PM comes and I don’t feel crabby or exhausted.

In fact, I am a bit elated. The South Beach Dieters must be on to something: protein does make a difference in staving off hunger.

I’m not sure if it’s the new approach to breakfast or just the fact that my body has adjusted to the feast-or-famine food schedule, but things begin to look up. I have energy again. In fact, I have more energy than I’m used to in the dead of winter, the season when darkness creeps forward to gate-crash my life. The worst part is always the lack of sunlight, of rising in shadows and pushing through the long winter evenings. This year, by contrast, I welcome the redemptive darkness as a friend. Darkness is when the comforts of life—sleep and food—are most available to me. As I settle into a rhythm of the fast, I feel like I’ve conquered the DTs enough after the first week that I’m ready to think about spiritual questions. So far, my fast has been more like an episode of Survivor than a religious quest, with little energy for anything but getting through the day. It’s time to go deeper.

FASTING WITH THE DESERT PARENTS

“So, have you had any visions yet?” a Christian friend asks me in my second week of fasting.

“Only of casseroles,” I reply, trying to keep things lighthearted. In truth I am surprised by the question, and by the fact that it keeps coming up. Several people want to know whether it’s true that fasting engenders trippy visions of God or the devil.

It’s not true, at least for me, but there’s a part of me that wishes for some dramatic manifestation, a divine response to this sacrifice. There’s certainly a tradition in Christianity that shows God visiting people with extraordinary spiritual visions when they fast. Whether that’s from calorie-deprived hallucination or a heightened spiritual sensitivity is anyone’s guess.

But if there’s too much emphasis on the fantastic, some of the fault lies with the Desert Parents, a number of whom were extremists. In history, the timing of the Desert Parents’ exodus into the hinterlands of Egypt in the third and fourth centuries happened not long after the Roman Empire stopped killing Christians for sport. Were some of these Fathers and Mothers the same types who would have gladly served God by becoming lunch for lions? Maybe when the extremists were deprived of these more sudden and public routes to martyrdom, they skipped town for the desert and a new life of hermithood. One of them allegedly subsisted on the nutrients of a single pea, praising God for the miracle. They strove to model themselves after John the Baptist. I hate to remind them that things didn’t exactly end well for John.

Other Desert Parents, thankfully, took a more middle-of-the-road approach, so these are the ones I focus on. Gregory the Theologian wrote, “There are three things that God requires of all the baptized: right faith in the heart, truth on the tongue, and temperance in the body.” I chew on that list several times before committing it to my quote book. It sounds so sane. Doable, even. Cultivate faith; tell the truth; don’t be ruled by your appetites. There’s still plenty of room in that configuration for enjoying life to the fullest and loving family and friends. These are words to live by.

I also like the attitude of Theodora of the Desert. Theodora was a renowned ascetic in the late third century; monks and other people would travel from afar to hear her wisdom. Once the wife of a high-ranking tribune, she renounced all her wealth and position and died a penniless beggar. If anyone could have exercised a little puffery about fasting, it would be Theodora; she was an expert. But she didn’t teach that. Instead, she told a story about a desert monk who had learned the secret to banishing demons. Would fasting make them go away, he asked the demons? No dice. “We do not eat or drink,” replied the demons. Was it all-night prayer vigils, then? Nope—the demons did not require sleep. How about separation from the world? Hardly. If the demons were having this conversation with the monk out in the desert, hadn’t they already followed him to the back of beyond? Then the demons released their bombshell: “Nothing can overcome us, but only humility.” Mother Theodora wanted her listeners to know that while fasting, prayer, and abstinence from the world were all very well, those practices could easily be perverted into self-righteousness and dead legalism if done for the wrong reasons.

The Desert Parents suggest that humility is the key to godly fasting. When a student asked the Desert Father Moses (not the Bible’s Moses—this was centuries later) what use fasting might be, Moses replied, “It makes the soul humble.” That’s

it. Fasting is not for visions or even for answers to prayer. It’s not to manipulate God into acting according to our wishes, and not to show God just how willing we are to sacrifice something for him. Fasting is to help us on that painful road toward humility. That’s why, in the Bible, so many of the instances of fasting occur hand in hand with mourning—the whole sackcloth-and-ashes bit.

Start by doing what is necessary, then do what’s possible;

and suddenly you are doing the impossible.

—ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI

MARS, VENUS, AND FASTING

As much as I like what the Desert Parents have to say about humility, fasting doesn’t make me more humble and less worldly. In fact, all this single-minded focus on the body may be having the opposite effect.

“Have you lost much weight yet?” women ask me. Many of the women I talk to—even ones I consider to be profoundly spiritual—tell me right away, in tones that are simultaneously apologetic and defensive, that they “could never do that.” Women admire the fasting but do not aspire to it. In contrast, many of the men seem to regard fasting as an extreme sport. They want to quantify my experience—How many days? How many pounds lost? Am I really abstaining from water as well as food? Several indicate they might want to try something similar. To them it’s a competitive dare, like swallowing termites or jumping off a cliff. Something for the bucket list.

When it comes to fasting, men and women may be Mars and Venus. During my month of fasting, Brookhaven National Laboratory released an interesting study about gender and food deprivation. Scientists interviewed groups of men and women about their favorite foods before having them fast from all food overnight. The next day, the famished study participants were shown a parade of the foods they had identified as their favorites, all while hooked up to brain monitors. Both the men and the women reported that they were able to successfully utilize certain mind-over-matter “cognitive inhibition” techniques to suppress their hunger while they saw and smelled pizza, chocolate chip cookies, and other delights. However, it seems that the women lied. Whereas the men’s brain scan results were consistent with what they reported—their brains were not responding in a dramatic way to the various food stimuli—the women reported being calm and collected while the food regions of their brains were actually hopping with exhilaration. “Even though the women said they were less hungry when trying to inhibit their response to the food, their brains were still firing away in the regions that control the drive to eat,” said the lead scientist.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood