- Home

- Jana Reiss

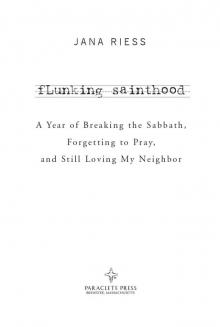

Flunking Sainthood Page 4

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 4

I understand that’s not true for everyone. I’m fascinated by how many Americans seem to have the all-singing, all-dancing kitchen but rarely cook in it. They eat out and order in, but don’t actually produce much on their coveted stainless steel Wolf ranges. When I watch HGTV programs like House Hunters, I’m struck by the number of home shoppers who imagine that they will start cooking one day, but only when they have a gleaming, spacious kitchen like the one in house number three, whose center island could double as a helicopter landing pad.

If I feel superior on this point, it’s because cooking is one of the only household chores I look forward to. But the sticking point with Brother Lawrence is that it’s not just cooking where we’re supposed to find God; it’s in any menial task. I’m surprised to learn that Brother Lawrence confessed to his abbot that he had a “natural aversion” to kitchen work. In my mind I had pictured him as one of those James Beard types who realized his culinary calling in childhood. Brother Lawrence was French, after all. Apparently they do food rather well there. But no, it was not the actual creation of a meal that was special to him. Nowhere in the book does he or his biographer talk about Lawrence’s love for cooking or his gravitation toward the comforting smells of stew and bread; in fact, considering how famous Lawrence is for being the great sacralizer of culinary chores, there’s very little in here about the manual labor for which he was most famous.

Instead, his only thought was “about doing little things for the love of God, since he was not capable of doing great things.” Brother Lawrence sought God in everyday tasks, which became for him conduits to the divine. Cooking, cleaning, shopping, cobbling shoes—the task itself was immaterial. What matters to God, Lawrence taught, is the love we express while doing it.

A dairymaid can milk cows to the glory of God.

—MARTIN LUTHER

So I am going to have to get out of my comfort zone and do more than flip a few pancakes for the Almighty. Where to begin? I start making a list of the household tasks I do every day, every week, and less regularly. As I do this, I’m astounded to see how much of my life is spent simply maintaining the status quo. Most days I cook, wash dishes, and pick up the house; every week I do the laundry, vacuum, pay the bills, go to the grocery store, and take care of our forlorn houseplants, among other things. Phil helps with some of these chores and has many of his own, but since he’s gone ten hours every weekday and I generally work from home, the bulk of the regular maintenance falls to me.

The trick this month will be to find some redemptive spiritual value in all those menial tasks. I tend to focus on the end result of any chore, getting it over with to enjoy a clean(er) kitchen floor. I’m not a fan of the process itself, which seems like something to grin and bear. It’s hard to get excited about the process when it simply repeats itself over and over: all of these are things I had to do yesterday or last week, and all are things I’ll need to do again tomorrow or next week.

The round of regular daily chores doesn’t even take into account the reality of how often things fall apart. Right now, Phil and I ought to find someone to upgrade our chimney, which has no cap. Although I’ve forbidden Phil from getting on the roof, he takes care of most of the other entropy as things break down in the house and the yard. Luckily for me—at least most of the time—he is a classic DIYer, the kind who would gladly perform his own vasectomy using a Time-Life home surgery manual if he could save a buck. He fixes computers, lays tile, hangs drywall, repairs cars, and stitches up ailing beanie babies who’ve lost their stuffing. His basement “man cave” has a sewing machine always at the ready, because really, what man cave would be complete without a sewing machine?

When our daughter was small, Phil’s job required a good deal of travel, and it was inevitable that on the first day of a ten-day trip to Japan or Italy or someplace equally inaccessible, an appliance would break down at home. It was astonishing how reliably this disaster would recur. He went to Germany, and the dishwasher started spewing soapy water on the kitchen floor. He flew to France for a long weekend—hey, it was a very difficult job—and suddenly there was no computer connection and the car wouldn’t start.

After about two years of this I finally commented to him how exasperating it was that every appliance conspired to make my life miserable each time he removed his passport from its file. Then he explained something I honestly had not noticed: things were actually breaking down all the time, not just when he headed out the door. He hadn’t seen the need to worry me about most of them, so he quietly went about fixing them, sometimes after I’d already gone to bed, like an oversized elf engineer.

GOD IN AN APRON

God is like that, repairing the world all the time. Even though it’s hard for me to see the spiritual value in menial household chores, there’s something deeply Christian about them. In a brilliant book about the theology of housekeeping, Margaret Kim Peterson says that it’s precisely the never-ending nature of household tasks such as cooking that makes them “so akin to the providential work of God.” Every day, every person in the household needs to be fed—again. We feed them with the knowledge that tomorrow morning, they will wake up hungry and we’ll have to repeat the whole cycle.

Peterson says that our constant round of housework and God’s initial act of creation have something in common: both are about bringing order from chaos. But God doesn’t just put our earthly home into motion and let things take their course; he’s constantly playing housekeeper. We see this in the Bible. When Adam and Eve are exiled from the garden and have to strike out on their own, God’s first act is to clothe them. He gives the kvetching Israelites manna from heaven to snack on during their forty-year nature hike. He also becomes increasingly domesticated throughout the Old Testament, dwelling first in an ark, then a tabernacle, and finally a temple—a great biblical example of trading up, real estate wise, from a mobile home to a mansion.

God’s son, Jesus, is also concerned with daily life and domestic cares, even though he cautions us not to be too anxious about them and chides his friend Martha when she freaks out about household duties. Jesus says that anyone who clothes the naked and feeds the hungry is also doing these same services for him—an interesting reproof to anyone who’s apt to dismiss cooking and shopping as meaningless tasks. He compares the kingdom to a banquet and suggests that God wants every seat at the feast to be occupied; he teaches his disciples to pray to God for their daily bread, sanctifying that most basic human need. Even God’s incarnation in Jesus might suggest something startling about the importance of housework: like housework, redemption is physical. God doesn’t stand around watching humanity go to hell in a handbasket; he gets his own hands dirty by sending his Son to heave us from the muck. In Jesus, God is cleaning his house.

I’m fascinated by the way Peterson deals with the endless, repetitive nature of housework and how unsatisfying it can be, especially when we look at our homes and only see the tufts of dog hair adorning each corner, or the Tang-like orange band at the bottom of the shower liner. “All the more is this so when our homes are not all we might wish them to be. God’s world is not as he wishes it to be, either,” she writes. Touché.

With a new awareness, both painful and humorous, I begin to understand why the saints were rarely married women.

—ANNE MORROW LINDBERGH

For Peterson, the importance in these repetitive chores is that they compose a litany of prayer. In church life, a litany is any kind of familiar, repeated prayer. In my husband’s Episcopal liturgy, it’s the communal prayer that alternates between the reader and the congregation. The reader petitions for the environment, for social justice, or for more far-reaching NPR reception, like any self-respecting liberal Episcopal church. The congregation occasionally proves that it is still awake by droning at prescribed intervals, “Lordhearourprayer.” That’s a litany. The prayers change slightly, reflecting whether a congregant at the retirement home is sick or Minnie Olsworth had her C-section, but the responses, the timing, the basic

structure are always the same. There is a comfortable familiarity in the routine.

According to Peterson, housework is precisely like this. A well-run household has a basic mealtime and some usual players, although the times and the diners may change depending on circumstance. The structure of the meal usually follows a prescribed path—salad, main course with side dish, and dessert if you don’t have kids; chicken nuggets consumed only under threat of the absence of dessert if you do. And during it all—from the hour of preparation to the ten minutes of consumption and twenty minutes of cleanup before you all head out to piano lessons—there is the opportunity for prayer.

MINDFULNESS

In Brother Lawrence’s world, as in mine, daily cooking was a given. The difference between us is that he saw cooking as an opportunity to become one with the Lord of the Universe, whereas I see it as the one snatch of my day when I can listen to All Things Considered. Cooking is allegedly the perfect hand-occupant during times of prayer because of its repetitive nature; the fact that I’ve made corn chowder so many times before means that I know the recipe by heart and can focus instead on God. Or at least that’s the theory.

In practice I learn the very first week that this kind of spiritual multitasking feels artificial. I cook the meals, wash the entry hall floor—sullied by a film of rock salt and melted snow—and clean the house’s one working bathroom. (The other is our ongoing renovation project, which is a spiritual discipline all in itself.) I do these chores in silence, but instead of enjoying the quiet as an accompaniment to my growing spiritual bliss, my mind zips around like the bamboo plants we keep trying to kill off in the backyard, which preserve themselves by sending off industrious, hardy shoots all the way to the other end of the lawn. My mind cannot stay present in the moment.

And that’s when I at least attempt to be mindful of God and do chores; sometimes I skip out altogether. When my friend Alice mentions that she needs to clean her oven and is dreading it, I volunteer for the job before I quite know what I’m saying. She has a new baby and could use some help around the house. Since I’ve never actually cleaned an oven before, not once, I read up in Home Comforts about what’s involved. It sounds like a boatload of hot, smelly work. How am I going to find God in this chore? Surely a quicker route to genuine religious experience would be to snort the spray cleaner and get high on the fumes.

Although I’m ashamed to admit it, nothing ever comes of my spontaneous offer to clean Alice’s oven. I propose a date, but it doesn’t work for her; I promise I’ll get back to her and just . . . don’t. When I next see her, she has either forgotten the offer or is too polite to mention my failure to follow through.

Although oven cleaning is a concrete practice, it’s still unclear to me what it has to do with spiritual growth. This month’s endeavor to “practice the presence of God” feels vague. What does that phrase even mean? I still have no idea what I’m supposed to be doing, and dear Brother Lawrence isn’t exactly helping. I mine the book for details, trying to learn how he accomplished his perpetual feat of Kitchen Zen. However, seventeenth-century hagiography is not the most appropriate genre for learning how Brother Lawrence cultivated his heightened spiritual state. The book’s editor derives an inordinate amount of pleasure from describing how Lawrence suffered from gout, an ulcer, pleurisy, and other illnesses that refined his soul and fitted him for heaven, yada yada yada. But I’m not finding “The Five Steps Toward Oneness with God” that I’m hoping for. There’s no checklist of things to do so I can follow in Lawrence’s footsteps. It’s only near the back of the book that I find this promising start to one of Lawrence’s letters:

Great peace is found in little busy-ness.

—GEOFFREY CHAUCER

To the Reverend Mother N . . .

Since you have expressed such an eager desire to have me share with you the method I have used to arrive at that state of the presence of God in which our Lord by His mercy was willing to place me, I cannot conceal from you that it is with great reluctance that I allow myself to be won over by your persistence. I am writing only under any condition that you will not share my letter with anyone.

Well, bully for the Reverend Mother that she pushed him for some answers beyond his usual platitudes about “just practice God’s presence every day,” and also didn’t take Lawrence’s suggestion that she should burn the letter after reading. I like this lady.

This Reverend Mother continued to exchange letters with Lawrence despite her failing health, which should earn her kudos because Lawrence appears to have been an exasperating correspondent. I’m beyond irritated by his tendency to downplay her illness and obvious physical pain. “If we were quite used to practicing the presence of God, all sickness of the body would seem trivial to us,” he lectures her. In other words, if your faith were only stronger, you’d be so holy you wouldn’t notice the pain. Brother Lawrence’s bedside manner gets worse: “I cannot understand how a soul who is with God and who wants only him is capable of suffering. My own experience proves this.” So not only is the Reverend Mother’s faith insufficient because she still endures some physical complaints, but Brother Lawrence’s is perfect. The guy is now ticking me off.

So I stop reading his book and go rogue. One day when I’m alone in the house, I head into the kitchen to make cookie dough and begin simply talking to Jesus.

“You know, you don’t have to give me the silent treatment,” I challenge him. “Throw me a bone here!”

I’m not sure why I pick Jesus rather than God; Brother Lawrence hardly speaks of Jesus at all. But Jesus seems less abstract, more accessible. I like the idea of him pulling up a barstool to the laminate countertop and listening to me prattle on about my day. His head would be cocked slightly to the right, an eyebrow occasionally raised in interest. He would gratefully eat a sample of cookie dough, because the Son of Man doesn’t have to worry about getting salmonella from raw eggs. He would mostly listen, asking the occasional probing question. He would lead me gently toward loving action without pointing out the inadequacies of my personal faith, as Brother Lawrence seems wont to do.

So I talk to Jesus. I confide aloud my anxieties about a family member, and unload about a problem at work. Girlfriend stuff. I don’t tell Jesus how amazing he is, or do anything remotely worshipful. The experience is wholly self-centered, which is probably why it’s the only time I’ve succeeded in staying in the present moment the entire month.

For prayer is nothing more than being on terms of friendship with God.

—TERESA OF AVILA

After a few days of this, the mindfulness practice gets a tad easier. “We must not be surprised at failing frequently in the beginning,” Lawrence advises. That’s an understatement. It’s a good thing that I’m talking out loud to Jesus, because my mind is still like a sieve. It isn’t until nearly the end of the month, after I’ve gotten more used to chatting up the Son in my kitchen, that I consult Brother Lawrence again and read the advice he gave to an admirer who wrote to him sometimes. He admonished her never to pray aloud: “Long speeches often become an occasion for straying.” Jeepers, I just can’t win. The one variation on mindfulness practice that has proven helpful is something Brother Lawrence IDs as a failure. Whatever.

FAILED SAINTS

Even though I find Brother Lawrence annoying in practice, I admit his spirituality is appealing in the abstract. There’s something very American (and un-French) about assigning such godly and redemptive attributes to daily work. Lawrence, I am realizing, could be the patron saint of the 1950s American housewife, if he only wielded a Sunbeam blender and donned a chintz apron over his cassock.

Except that Brother Lawrence was never made a saint. I don’t realize this until nearly the close of my unsuccessful month of mindfulness, and this piece of information increases my sympathy for him. I may not like him much myself, but my heart leaps up in loyalty to defend the guy. Not an official saint! This is a serious oversight that I mean to bring to the attention of the pope just as soon as I a

m retired and have time to pontificate via complaint letters. There are more than 2,500 entries in Butler’s Encyclopedia of Saints, and some of them sound downright lame. I mean, for every St. George slaying a dragon and Perpetua getting bloodied in the lion’s den, there are no-names like Frumentias of Ethiopia. Excuse me, Frumentias? And then there are the saints that are positively certifiable, like Christina the Astonishing, who was apparently astonishing in that she was flat-out weird. She could not tolerate the stench of other human beings (which was understandable—this was the Middle Ages after all), and basically terrorized the village as that crazy homeless woman who yells at everyone passing by. If Christina gets saintly props for being an early candidate for Bellevue, why not sweet Brother Lawrence?

“It isn’t fair,” I vent to my colleague Anna, who is sort of Catholic. (I say “sort of” because she grew up Catholic, never goes to church anymore, and has little good to say about it herself, but if she catches other people talking smack about the Holy See, she jumps on them with the fervor of a new convert.) “Brother Lawrence cleaned up after all those monks for years and did their grocery shopping and even fashioned their shoes. Why do all these other turkeys get to be saints and not him? He peeled their potatoes and took care of them when they were sick!” Okay, I don’t actually know about that last part, but maybe he nurtured the sick when he wasn’t telling them their illness was their own fault.

“What were his miracles?” she asks with some interest.

“His miracles? Um, I’m not sure. Isn’t feeding a whole monastery for years on nothing but a kitchen garden kind of a miracle?”

Anna is unimpressed. “Well, if that’s a miracle, then my grandma should be canonized too. She raised eight kids with no money and an alcoholic husband, and those kids all went to college.”

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood