- Home

- Jana Reiss

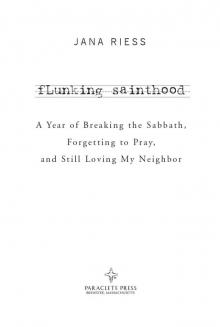

Flunking Sainthood Page 17

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 17

Day’s decades as a Catholic, from the mid-1920s until her death in 1980, fueled a fiery combination of progressive social causes like antiwar activism and hunger relief with traditional Catholic piety. She and her mentor, Peter Maurin, founded the Catholic Worker movement, which advocated for the poor and founded houses of hospitality in American cities. Not surprisingly, the movement’s growth exploded during the Great Depression in the 1930s. Day lived in voluntary poverty so she could pour all of her energy back into the movement. “Voluntary poverty means a good deal of discomfort in these houses of ours,” she wrote. “Many of the houses throughout the country are without central heating and have to be warmed by stoves in winter. There are backyard toilets for some even now [in 1951].”

Reading Dorothy Day during my $4,000 charity experiment is like fetching ice cubes from the freezer just before being told you’re actually supposed to generate an entire glacier instead. Suddenly nothing I am attempting seems good enough. What is tithing, when Jesus told the rich young man in Luke 18 to sell all that he had and give the money to the poor? What good does it accomplish to raise $4,000 for people I’ll never even meet (and if I am honest with myself, don’t particularly want to meet)? Just as with the hospitality experiment, I have carefully controlled the parameters of this month’s spiritual practice. I want to give to strangers with the click of a mouse, not get involved in their thorny lives. My own life is complicated enough.

It is easy to love the people far away. It is not always easy to love those close to us. It is easier to give a cup of rice to relieve hunger than to relieve the loneliness and pain of someone unloved in our own home. Bring love into your home for this is where our love for each other must start.

—MOTHER TERESA

Dorothy Day wrote compassionately about people like me, failed and failing saints who, like that rich young man in the Gospel of Luke, could never quite sacrifice our ease and comfort to follow Jesus. “You can strip yourself, you can be stripped, but still you will reach out like an octopus to seek your own comfort, your untroubled time, your ease, your refreshment,” she wrote. I am that octopus. One leg writes a check to alleviate other people’s poverty while seven others procure my family’s food, bedding, vacations, comfortable clothes, entertainment, furnishings, and transportation. By the standards of my own culture, none of this is ostentatious. In fact, as I smugly pointed out in chapter 5, compared to some, our family lives fairly simply. But am I prepared to sell our house, donate the proceeds to the poor, and embrace voluntary poverty in order to serve God? No way.

In fact, I haven’t even managed to raise my $4,000 after all. When I settle accounts at year’s end and add up all of the charitable donations I made with the ones my friends offered for my birthday, the total is $3,651.47. That’s close, but I didn’t quite meet the goal. I’m like those people I criticized in Christian Smith’s book, the ones who succumb to the “social desirability bias” by overestimating their own generosity.

“I’m really sorry, Jesus,” I mutter out loud. I’m walking up Vine Street downtown, heading toward the public library a few days after Christmas with my hands thrust deep into my coat pockets.

“Ma’am, can you help me out some here? I’d appreciate some change.” The woman is sitting at the edge of the brick wall that encloses the main library’s courtyard, a sign in front of her saying, “HOMELESS. CAN YOU HELP?”

“Sure,” I say, scrambling in my purse to find a bill. If I’d remembered my resolve to give to everyone who asks before leaving the house, I could have had some cash in my pocket for such a time as this. As it is, we chat while I hunt for my wallet.

“It shooore is cold out here today. So you like the library?” she asks suddenly. I look her in the face for the first time. She has chocolate skin and a brown ski jacket of the same hue, those muted shades providing background for a riotously colored green and red reindeer hat with jingle bells dangling from the ends of each antler.

“Yeah, it’s one of my favorite places anywhere,” I reply, giving her a grubby five dollar bill. She smiles at this but makes no comment. She wants to talk politics now.

“Do you think Hillary would have made a good president?”

“Um, do you mean Hillary Clinton?” Barack Obama has been in office for nearly a year. I like Hillary as much as the next person—wait, make that far more than the next person, since most people basically hate her—but I think the presidency ship has sailed without her aboard. I say as much.

“You got that right!” She guffaws. “Mmm-hmmm. She ain’t never gonna be president now. But I think she’d be a good one. She don’t take shit from nobody. You have a great day now, lady, and God bless you!” Her reindeer antlers jingle gaily as she dismisses me with a jaunty wave.

Dorothy Day wrote a Christmas essay in 1945 when she talked about how Christ sometimes appears to people in the guise of the poor. We don’t give charity to them because they remind us of Christ, Day said, “but because they are Christ, asking us to find room for Him, exactly as He did at the first Christmas.” It occurs to me, retreating down Vine Street, that it would be just like Jesus to camouflage himself especially for me as a swearing reindeer lady with a love for Hillary Clinton. For a flash, a single instant, my charity isn’t charity but connection. I’ve made a connection.

“And a Meeeeeeery Christmas!” she calls behind me.

Epilogue

practice makes imperfect

Progress is not an illusion. It happens, but it is slow and

invariably disappointing.

—GEORGE ORWELL

Six weeks after I turned in this book, I received a surprising phone call. The father I had not seen or heard from in twenty-six years was dying in Mobile, Alabama. Could I come there to say good-bye? Oh, and one more little question: did I want the hospital to discontinue life support, since he was unresponsive and could not breathe on his own?

I was stunned. The day took on a surreal feeling as I called my husband, called the nurse, called the social worker, called the airlines. His condition was bad, the hospital told me. The pulmonologist wasn’t sure if he would even last the night. He was “actively dying” now, having been in the hospital for thirteen days with a progressively worsening COPD, a form of emphysema brought on by decades of smoking.

Within a few hours I got on a plane, and spent most of the flight thinking about the past.

My father left us on a Friday, though I didn’t know that at the time. I didn’t realize he was gone until Saturday morning, and even then I had a child’s faith that he’d come back. That certainty lasted for three days. Mom, ever a pushover for a mental health day from school, had allowed me to stay home the following Monday to avoid the prying eyes and awkward questions of my peers. She’d stayed home from work to get a handle on things. After running some errands, she returned home to find me making cookies in the kitchen to cheer myself up. Now she sat down at the table with a thud of finality and defeat. She had been to the bank, she told me through her tears. He had taken every cent. He would not be coming home.

As I traveled to Mobile, I replayed these scenes in detail for the first time in years. The shock, the pain of his sudden abandonment, the betrayal of knowing that he’d chosen to humiliate us still further by emptying the future of retirement for my mother and college for us kids, still stung. The selfishness of it. The shame.

“I’m not sure I can do this,” I told a friend I had called from the airport. I was crying full tilt now, my life upended a second time by this man. “I thought I had forgiven him and forgotten all this.”

“How could you forget it?” she countered. “He hurt you terribly. You were only a kid then, right?”

“I was fourteen then. I think I’m only about fourteen years old now,” I sobbed.

“If you turned around right now and went home, no one would think less of you. You don’t owe him anything. You are a good person even if you can’t do this,” she said.

“I feel like this is a test,” I confi

ded. “Today I find out whether I’m really a grown-up, and a Christian. What if I fail?”

I am not much holier than I was before I began, but I am still trying nonetheless.

—ROBERT BENSON

And so I prayed that God would give me peace and the wisdom to know what to say when I saw my father. By the time I arrived at the hospital, so late at night that I had to enter through the emergency room, a quiet peace pervaded every decision. Within moments I was at his side, shocked at his wizened appearance despite the nurse’s warnings over the telephone that he would look far older than his actual age of seventy-one. Shrunken and gaunt, this 117-pound man with the breathing tube didn’t seem like he could be the larger-than-life specter I remembered from my childhood. He looked piteous, and it was not difficult to find sympathy crowding out every other emotion. Only his famous beak-like nose had retained its full glory.

Dad lasted two more days, and passed away with my brother John at his side describing some of the twists and turns his life had taken after Dad left us. As John talked to him, a cardinal fluttered outside the window, catching John’s attention. He hadn’t realized there would be cardinals in Alabama in October. When he looked back at my father, the labored breathing slowed and stopped. Dad was gone.

Here is what I learned from my father’s sudden reappearance and death: all of those unsuccessful practices, those attempts at sainthood that felt like dismal failures at the time, actually took hold somehow. They helped to form me into the kind of person who could go to the bedside of someone who had harmed me and be able to say, “I forgive you, Dad. Go in peace.” Although I didn’t see it while I was doing the practices themselves or even while I was writing the chapters in this book, the power of spiritual practice is that it forges you stealthily, as you entertain angels unawares.

John, Phil, and I spent three days cleaning out my dad’s apartment, a toxic wasteland of papers, unwashed clothes, and vitamins stacked to the ceiling. Picking carefully through his things, we began to piece together the lost years of his life, and it was a sorry picture. The man who had left us with full vigor and a pocketful of cash had squandered his health on the smoking habit that would kill him and wasted his money on gambling and porn. Sadder still, there was no evidence anywhere of a friendship or any kind of personal relationship in the twenty-six years he’d been gone. He had chased the idea of making his body live forever, but hadn’t invested his heart in a single person. The two photographs we found in his apartment that had been taken since he left our family in 1984 were both of himself, snapped one night when he had a memorable winning hand at poker. That was all.

The life of the spirit is one lived for others. My dad, on the other hand, lived opposed to this principle: he was a grasper, always reaching beyond his present circumstances to chase a dream of easy wealth (we found every conceivable get-rich-quick scheme in his files) or restored youth. He did not invest in eternity. I’m sure that God has forgiven my dad, and I can write with honesty that I have forgiven him too. But I don’t want my world to be like his. One way to live the life of the spirit, and offer it to God and others, is through spiritual practices—my daily commitment to implementing a different kind of life.

All through this project I’ve been hard on myself because of the practices I couldn’t do at all (Centering Prayer), the ones I did successfully but pridefully or for the wrong reasons (fasting), and the ones I didn’t quite see the point of (Brother Lawrence’s mindfulness). But in the end, many of this year’s practices helped me when I needed it the most: fasting helped to teach me that this body and this life are not all there is, that there is a life of the spirit beyond food and health and the hundreds of bottles of vitamins we cleared out of Dad’s apartment. While I already knew this with my head—I’ve been a Christian for many years, and I know the drill about eternal perspective—still I didn’t understand it in the core of my body. Now I do. I didn’t fast perfectly, but I also didn’t flunk that practice. I came to understand, viscerally, the larger points: God is infinite; this life is a proverbial drop in the bucket; we are but dust. Fasting is a potent bodily reminder of these things.

Sabbath keeping taught me about time out of time. It occurred to me as I dropped everything to be at my father’s bedside that when we truly keep the Sabbath, God can mold us into the kind of people who don’t make an idol out of work, which is a particular temptation for me and perhaps a lot of other Americans. Sabbath time is like suspended animation, which is also how everything feels when the death of someone we love topples all our plans. Other practices I attempted, especially fixed-hour prayer, have this same undercurrent. Your schedule is all very well, these practices say. But you have to be prepared to drop everything for God, for others, for death.

After a death, though, we slowly regroup. We spend a few weeks or months in mourning and then gradually move on with our daily lives, never forgetting the person we loved but quite easily forgetting the way death’s intrusion reminded us of our own mortality and unimportance. The Sabbath doesn’t allow that, however. It’s an enforced weekly shutdown of all our pretensions, a glimpse of eternity in the everyday.

I don’t have a tidy moral for each of the practices I tried. One of the main lessons I learned this year, in fact, was that I was delusional for imagining I could master any spiritual practice in thirty days. If I had it all to do over again, I would allow for more time. Like, say, a five-year plan. I was also an idiot for trying so much of this by myself rather than in community. Spiritual practices help the individual, sure, but it takes a shtetl to raise a mensch. There’s a particular kind of hubris in the DIY approach I took to all of these spiritual practices, most of which weren’t intended to be tried alone.

And if I did it all again, I would try to stop practicing charity from a distance. One of my greatest failures this year was my careful refusal to get involved. In September, my hospitality was practiced primarily on people I already knew; in December, my generosity was expended on people I would never know. Both were easier, far easier, than welcoming the stranger. But it’s the act of loving that marks the true saint. And I was able to love my dad, there at the end of his life. I sat by his bedside, held his hand, and prayed the Jesus Prayer for both of us. LordjesuschristsonofGodhavemercyonmeasinner.

If we look for Christ only in the saints, we shall miss Him. . . . If we look for Him in ourselves, in what we imagine to be the good in us, we shall begin in presumption and end in despair.

—CARYLL HOUSELANDER

These are small outcomes from practices that were done far from perfectly. In a culture that stresses perfection, I’ve often heard the maxim that “good is the enemy of perfect”; in other words, when people of faith aim for anything short of godliness we miss the mark. I’ve learned the reverse is true: perfect is the enemy of good. I may have spent a year flunking sainthood, but along the way I’ve had unexpected epiphanies and wild glimpses of the holy I would never have experienced without these crazy practices. A failed saint is still a saint. I claim that S-word for myself, even with all my letdowns. I turn to Dorothy Day here, who said that we are all called to be saints, “and we might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name. We might also get used to recognizing the fact that there is some of the saint in all of us. Inasmuch as we are growing, putting off the old [self] and putting on Christ, there is some of the saint, the holy, the divine right there.”

Notes

Chapter 1: choosing practices

Another version of Lucy’s story says that Roman guards dug out her eyes with a fork. Also unappealing.

Lauren Winner’s thoughts on the wording in Exodus are from Mudhouse Sabbath (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2003), ix–x. Abraham Joshua Heschel’s quote about the “ecstasy of deeds” is found in God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1976), 283.

Chapter 2: fasting in the desert

Gregory the Theologian is quoted in Eternal Wisdom from the Desert: Writings from the Desert Fat

hers, ed. Henry L. Carrigan, Jr. (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2001), 87. That book is also the source of the story about Theodora of the Desert, pages 96–97, and the quote from Father Moses, page 113.

The Brookhaven study about men’s and women’s different tolerance levels for food deprivation is reported in “Evidence of Gender Differences in the Ability to Inhibit Brain Activation Elicited by Food Stimulation” at http://www.pnas.org/content/106/4/1249.full. You can also read about it in Randolph E. Schmid, “Study: Women Less Able to Suppress Hunger Than Men,” Huffington Post, January 20, 2009.

For more on the medieval women saints, see Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), esp. 25, 41–43, 76, 122, 138. On fasting and the diet culture, see Lynne M. Baab, Fasting: Spiritual Freedom Beyond Our Appetites (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 24–27 and 133–36.

Scot McKnight’s thoughts are from Fasting (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2009), esp. 19, 51, 117. Portions of my discussion of McKnight’s Fasting book appeared in a review I wrote for Explorefaith.org:

http://www.explorefaith.org/resources/books/fasting.php?ht=

“One can be damned alone” is quoted in Baab, Fasting, 60.

Synclectica’s advice about sleeping on the ground is found in The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated and introduced by Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1975), 232.

Chapter 3: meeting Jesus in the kitchen . . . or not

For more on Brother Lawrence, see the introduction to The Practice of the Presence of God, trans. Robert J. Edmonson, Christian Classics (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 1985), esp. 31–32, 38–39, 67–69, 100, 109, 112. Hannah Whitall Smith’s quote is found in the introduction to this book (p. 21), and Brother Lawrence’s correspondence with the Reverend Mother are in the chapter called “Letters” (pp. 79-120).

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood