- Home

- Jana Reiss

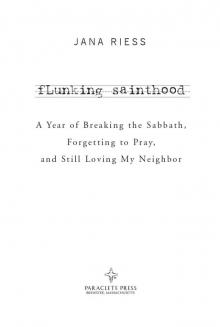

Flunking Sainthood Page 16

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 16

My stats for fixed-hour prayer are still dismal, so by ESPN standards, the month is another failure. In the thirty days of November, with seven prayer opportunities per day, I could have prayed the office 210 times. I’ve probably completed only a fifth of that. But numbers don’t tell the whole story: I feel closer to God and to the communion of saints. That’s got to count for something, because it feels like it means everything.

12

December

generosity

[Jesus] said that a glass of water given to a beggar was given to

Him. He made heaven hinge on the way we act toward Him in

His disguise of commonplace, frail, ordinary humanity.

—DOROTHY DAY

“Um, Mrs. Smith? May I please speak to Mrs. Smith?”

That’s when I know I am screwed. The only people who call me Mrs. Smith are strangers who don’t realize that my husband and I, in a fit of impractical postcollegiate egalitarianism, both kept our original last names when we got married. This starched voice belongs to a telemarketer, and the telemarketer must belong to a charity, because all noncharitable telemarketers are blocked from dialing our telephone number. Normally, I would simply thank him for calling, announce in a crisp tone that our family does not accept telephone solicitation, and hang up the phone before he can chime in about saving puppies or the planet. But today I cannot. This is the first day of December, so I must hear his spiel to the bitter end. Then I’ll be obliged to give him something.

It’s my month of radical generosity, of giving liberally to all who ask. This comes from the Gospel of Luke, one of those inconvenient passages I try not to think about:

And unto him that smiteth thee on the one cheek offer also the other; and him that taketh away thy cloak forbid not to take thy coat also. Give to every man that asketh of thee; and of him that taketh away thy goods ask them not again. (Luke 6:29–30 KJV)

For December I am putting this verse into action by becoming a girl who just can’t say no. And like the one in the Broadway musical, I can already see that I’m in a terrible fix. I am going to have to say yes to this stranger on the phone. What will it be this time? The firemen’s ball?

“Um, ma’am? Is this Mrs. Smith?” the über-polite voice persists.

“Yes,” I respond weakly. “This is Mrs. Smith. How can I help you?”

“As you know, Mrs. Smith, so many children today are being diagnosed with rare and terrible cancers. The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society would like to be able to count on your help.”

Oh my Lord, I think. He’s going to ask me to run the friggin’ marathon. “Since you’ve been so generous to us in the past”—which is generous of him to say of my microscopic and erratic donations—“we would like to ask you to be a neighborhood cheerleader for the society. If we send you some fundraising letters and envelopes, could you address them and distribute them to your neighbors?”

That’s it? I exhale with wild relief and accept eagerly. “Yes! Yes, absolutely I can do that.” There is a brief silence on the other end while he contemplates the sincerity of my 180-degree turnaround from appeal dodger to MVP for the Kids. But I had been sure he was about to ask me to run the marathon, since my earlier donations had come when various well-toned friends had pounded the pavement to fight children’s cancers. I was content to support them from the background, writing checks while munching on Oreos. Addressing a few envelopes seems like an awfully small request compared to twenty-six miles of hellish agony.

My goals for this month are two:

1) to give to anyone who asks (and I do mean anyone, so as I continue my haphazard November practice of praying the hours I insert a few ad hoc petitions that I not be solicited by the KKK, Rush Limbaugh, or the John Birch Society, on the far right; or anything to do with Al Franken’s new political career, on the left); and

2) to raise $4,000 for charity. This last goal is in conjunction with my fortieth birthday this month. The birthday feels significant; a corner is being turned away from young adulthood and into middle age. I’m far from having a midlife crisis, but I do sense a settling weight of yearning, or wanting my life to have mattered to more people than my immediate circle of family and friends. I also feel, at this threshold of forty, tremendously blessed in said family and friends. I want to give back.

BE THE CHANGE

On December 1 I log on to Facebook to register for a brand new way to pester my friends. Inspired by a blogger I know named Jana (yes, a different Jana), I want to use Facebook Causes to ask my friends for charitable contributions in honor of my birthday. Earlier this year, Jana, who lost one of her legs to cancer as a teenager and now walks with a prosthetic, raised money for state-of-the-art prosthetics for a twelve-year-old girl in China who had lost both of her legs in the Sichuan earthquake. Jana’s original goal was $380 in honor of her thirty-eighth birthday. This was increased to $600 and then $1,000 after friends’ donations poured in. I think all of us donors felt the power of what Jana was doing; we were raising money for a cause that was important to her, but we were also celebrating her survival.

How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.

—ANNE FRANK

What I didn’t realize was that Facebook would make me choose just one cause. Do I want to stop violence in Darfur, or cure cancer? Do I want children born with a cleft palate to have access to surgery, or to save the arts in public schools? Faced with so many needs, it’s hard to know where our donations might make the most difference.

I finally decide on the Heifer Project International. My conservative friends will poo-poo this as a circuitous way for liberals to imagine they are improving the lives of people they’ll never meet. My liberal friends will chafe at the consumerist mentality Heifer has, in which donors “buy” an animal for a community in the developing world (or, if we’re really swinging out, a whole flock). And that’s not even considering the folks I probably offended in chapter 10 by my inability to become a vegetarian, the ones who will be horrified that Heifer teaches people how to raise animals for meat as well as wool and eggs. (“The Heifer Project literally puts a price on animals’ heads,” sniffs one animal rights website.) In short, the Heifer Project has something to offend everyone even while doing good in the world. That makes it my kind of Flunking Sainthood charity.

It feels strange and a bit uncomfortable to lobby my friends for money. Are they going to resent this? Will my request be artfully ignored? I draft a letter that I send out to all my Facebook friends over the next several days:

Friends,

As many of you know, I am writing a book for which I take on a new wacky spiritual practice each month. Well, it’s December, which is the season of giving, right? So in the spirit of the holidays, and in honor of my 40th birthday, I am trying to raise a total of $4,000 for various charities, one of which is Heifer Project International (heifer.org). Heifer has been helping families become self-sustaining for 65 years. For just $10 you can buy a share of a goat to help a hungry family. For $120 you can go hog wild and purchase a whole pig!

Won’t you please take a moment to make a small donation in honor of my 40th? I don’t want gifts or cards. I want you to buy some chickens, people! (And I promise not to do this every year.)

I set my fundraising goal at $800, seal the deal by buying a pig, and wait for my friends to respond.

My sweet friends outdo one another in zeal, as the Scripture says (Rom. 12:10). By the end of the first day of December I’m already a quarter of the way there, and within a week I’ve zipped past the $800 goal. All in all, thirty of my friends cough up $1,160 on Facebook. According to the charity’s website, that means we have provided the equivalent of a water buffalo, a pig, a sheep, a llama, and a goat; four flocks of chicks, four of geese, and four of ducks; two trios of rabbits; and three hives of honeybees. Heifer also e-mails me on Christmas Day to say that its whole Facebook fundraising effort for December has netted $1,758 so far, which means th

at my own fundraising accounts for about two-thirds of their Facebook totals. Granted, Facebook obviously represents a minuscule part of Heifer’s global fundraising strategy, especially at the holidays, but here’s the thing: I feel fantastic.

This is the best birthday month ever! Often in the busy weeks of December, I experience a vague unease about the impending holiday season. It’s a familiar conundrum: we pledge that Christmas will be less commercial and more spiritual, then watch in dismay as our efforts are obliterated in a single outing to Toys “R” Us. My mid-December birthday is usually spent shopping, baking, and wrapping and shipping packages. This year, though, I put the lists away, build a fire in the fireplace, and roast s’mores with my family. This respite occurs in part because my birthday falls on a Sunday, which I’m still trying to keep as a Sabbath. (Although I doubt that rabbis would approve of the open flame, the fire contributes to the overall sense of shalom.) Larger than the actual day of celebration is the general spirit of unexpected calm that has settled around me. I know this tranquility has to do with the generosity project.

I’m not alone in my charitable deeds, which is a welcome change from most of the other spiritual practices I’ve attempted this year. In addition to the solidarity on Facebook, the company where I work part-time has forgone a Secret Santa gift exchange for fellow employees in favor of nonrandom acts of kindness this year. Under the new rules, we receive the name of a person, but it’s no longer someone to buy little gifts for (which is a relief because it’s always agonizing to find tchotchkes with the right personal touch). Instead we quietly scurry around doing five good deeds in that person’s name. People make donations to “Dare to Care” and the “Blessings in a Backpack” program, and send cards and letters to soldiers overseas. One person gets four colleagues to sign their organ donor intentions on the back of their drivers’ licenses, and someone else knits scarves for a homeless shelter. At the annual holiday party, amid karaoke and Mexican food, we learn the identities of our Secret Santas. Mine has made a donation in my name to the seminary I attended.

Teach us to give and not to count the cost.

—IGNATIUS LOYOLA

There also seem to be opportunities to give at the check-out line of almost every kind of store. I go to Blockbuster video, and they’re collecting for St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital. Barnes & Noble wants me to buy a book for a child in the Big Brothers/Big Sisters program; I choose A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, one of my all-time favorite reads. When I stop at Petsmart to buy dog food, they want financial help caring for homeless dogs and cats. Plus there are the usual community appeals: the Giving Tree at Jerusha’s school, the toy drive at church. I contribute to my friends’ Facebook appeals for clean water and a cure for brain cancers.

In the end, though, I don’t respond to every appeal like I’m supposed to. It’s just too overwhelming: public television, public radio, the food bank, every educational institution we have ever attended. . . . I’m asked to help fight breast cancer and lung cancer and bipolar disorder. Even the Girl Scouts, who have apparently heard how much I like their cookies, make a pitch for their endowment fund. By Christmas week I’m certain that with all of these donations plus our regular tithing I’ve already met the $4,000 goal, so some of the pleas go unheeded in the rush right before and after the holiday. The one I feel most guilty about is a personal letter from someone I know who has started a foundation for kids in Ecuador and Guatemala. I’ve been to Guatemala; I can almost see the children’s faces. Yet I put the unanswered appeals in a pretty toile box with a lid and try not to think about them.

WHAT IF WE ALL PAID TITHING?

When I was twenty I worked at a Salvation Army camp for a summer. All of us counselors had a great time with the kids, so despite the long hours and a fundamentalist camp director who signed his memos, “Camping for the King!” it was a fun time. (Well, apart from the ulcer and all.)

But I had very little money. At the end of August I came home to Illinois to prepare for my senior year of college. My college was located in a frigid climate, and I no longer had a coat. I’d been meaning to buy one all summer to prepare for my return to Massachusetts, but never got around to it. I hadn’t paid tithing all summer, either, but had promised myself a couple of years earlier that I was going to try to take the 10 percent thing more seriously. When I sat down at the dining room table to pay my bills and figure out my financial situation before heading back to school, I had a dilemma: I could pay my tithing, or I could buy a winter coat.

I’d cleared about $1,000 for the whole summer of being a camp counselor, and only had $100 or so of it left after expenses (some of which, admittedly, were hardly necessities—unless it’s a necessity to attend the home games of the Milwaukee Brewers on days off). My conscience was tugging at me to act on faith and send that last hundred dollars out to bless the world even though I wouldn’t have any money left to buy a coat. I debated about this—what would a measly hundred bucks be able to accomplish? Why wasn’t there some kind of student discount on tithing—like that students only had to pay 5 percent instead of 10?

I plunged ahead in faith. I decided to send $50 checks to Compassion International and Bread for the World while putting the coat on a credit card—not the most prudent financial decision, but I was barely out of high school. What did I know?

Maybe more than I do now. When I found a coat, which was warm and lovely and cost $85, my mother unexpectedly swooped in and said she felt she ought to pay for it. Since I’d been paying for my own clothes for years, this generous act was quite remarkable, but I wasn’t one to look a gift horse in the mouth. I wore that coat for years, a snug reminder of my act of faith in giving a widow’s mite to help the poor.

Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.

—JOHN WESLEY

That’s my one tithing miracle story. I’m sure that many experienced Christians will have a problem with the tidiness of it. I know, I’ve never liked the mentality of “if you only give, God will make you prosper,” or “God will pay you back a hundredfold.” I don’t think that God works that way . . . except for this one time when he did. Maybe such graces are given to relatively young and inexperienced Christians because they need small miracles in order to continue in faith. Or maybe older, more experienced Christians have become just hardened enough that we no longer recognize the small miracles when they do occur.

I do know one thing: the world would change tremendously if more Christians would tithe. This month I revisit Christian Smith’s book Passing the Plate: Why American Christians Don’t Give Away More Money. Its research is a big fat indictment of Americans who, by just about every standard of measurement, don’t give much money to charity. It surprises me because I had always heard that Americans were some of the most generous people in the world. If that’s true, then the world is in serious trouble.

The book makes some surprising conclusions about generosity. You’d think that people who earn higher salaries would give a higher percentage of their income than those lower on the totem pole. After all, these folks have a sizeable amount left over after paying for the basics of food, shelter, and clothing, right? Wrong. Those who earn more than $70,000 a year contribute, on average, only 1.2 percent of their income, which is half of the percentage contributed by those who earn under $10,000 a year. Giving goes down even further in those who earn more than $100,000 a year. It’s kind of crazy, actually: the wealthier we become, the more we forget the poor.

What’s especially depressing about these statistics is that because of something that sociologists call the “social desirability bias”—our innate desire to look better in the eyes of others than we actually are—many if not most of us actually overestimate how much we donate to charity. “It turns out that people have a tendency to say they give more money than it appears they actually do,” the authors conclude.

To me, the most exciting part of Christian Smith’s book is the opening chapter, which dares to dream about what could be accomplished if American Christians decided to tithe 10 percent of their after-tax income to the charities of their choice. There would be an estimated $46 billion—that’s billion with a B!—every year for philanthropy. The authors parse that out into dream piles: $4.6 billion could clothe, house, and feed every single refugee in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East; $350 million could provide scholarships for seminarians in the developing world. American Christians’ tithing could provide free eye exams and glasses to every child in poverty! We could make sure every person on the planet has access to clean water! I know the authors are just playing Fantasy Philanthropy here, but it’s exciting to start the book with a vision of the way things could be if Christians were more kingdom oriented, rather than the shabby state of things as they are.

ST. DOROTHY

Dorothy Day was that kind of visionary. I first encountered her writings in graduate school, when I read The Long Loneliness for a course on American women’s autobiography. In it she tells of her bohemian life during World War I and the early 1920s, of the men she lived with and the child she had out of wedlock—as well as the child she aborted. (That latter fact is why she’ll probably never become an official Catholic saint, even though she’s already one in popular imagination.) A socialist and labor activist, she was an unlikely choice for the twentieth century’s greatest American Catholic woman. Her conversion to Catholicism, beautifully described in the memoir, hinged upon a growing love of prayer and a continuing passion for justice, a zeal she carried over from her radical secular days.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood