- Home

- Jana Reiss

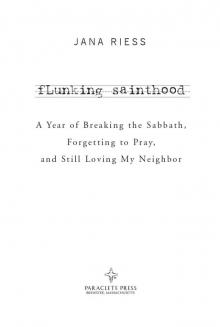

Flunking Sainthood Page 11

Flunking Sainthood Read online

Page 11

SUSTAINING GRATITUDE

Why are we so caught up with the idea of gratitude in the first place? Counting our blessings has become a Christian virtue right up there with prayer, worship, and eating green bean casserole at potlucks. Where did this come from?

Gratitude is not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all the others.

—CICERO

I read one study that agrees that gratitude can make us happier and healthier, but points out that it’s awfully hard to sustain over time. According to this theory, human beings are naturally adaptive creatures, and one of the evolutionary mechanisms that’s helped us to survive is our ability to become desensitized to anything but very recent changes. We’re wired to weather just about anything because we simply acclimate ourselves to new situations. That’s why we’re only fleetingly affected by positive changes—a raise, a weight loss, a new romance. After a while those beneficial developments are simply absorbed into the way things are. But there’s a silver lining: we can also adapt to tragic circumstances. Long-term paraplegics, for example, report the same basic levels of happiness as people with all their limbs. “When life falls apart, we’ll soon get used to it—such changes in circumstance don’t have to become incapacitating,” the study concludes. That’s the good news. “But when our lives are blessed, and things are going well, there seems something morally decrepit in how we so easily overlook how good we have it.”

Yes! That’s it. One of the things nagging at me this month is how I can’t seem to muster up any real gratitude about being healthy. I just don’t think about my good health that much, and when I write “health” in my gratitude journal, it’s mostly because that’s what I think I’m supposed to say. I feel guilty about this, especially because last year I had a little health scare. I went in for my first-ever mammogram and they found something. For the next month I had tests, including another (even more painful) mammogram and a needle biopsy that hurt like the devil.

At one point in the process my family doctor called me on my cell phone while I was out of town on business, telling me what the radiologist had already said: it didn’t look like breast cancer, but I should have the biopsy procedure just to be sure, given my family’s history. After I hung up the phone, I second-guessed every single thing she’d told me like a tween getting her first phone call from a boy. Did she really mean it when she said she didn’t think it was cancer? What was she not telling me? And why was she calling me on my cell phone on a Friday night?

So when the news finally came—no cancer had been discovered—I was giddy with relief. The weather that December day was gray, cold, and rainy, but I wanted to skip and pick daisies. I felt grateful for everything in my life—my health, my crazy family, my interesting job, my warm and comfortable house. Nothing bothered me.

That feeling of overwhelming gratitude lasted approximately 2.3 days. I tried to hold on to it, but gratitude is as slippery as trout. Ingratitude happened during the Christmas season, ironically enough. Somehow, during the days of decking the halls and baking the cookies, I lost that sense of the perfection of the now. I knew I had resumed normal life when I swore like a sailor at a driver who turned directly in front of me. Yep, I was back.

CREEPING REQUIREMENTS

As my month progresses I become increasingly aware of the everyday things I take for granted, and the knowledge depresses me. I’m also conscious of a little voice in my head that follows up any expression of gratitude with a secret unexpressed desire for more. On a long flight out West to speak at a conference, I’m unexpectedly upgraded to first class (it’s my lucky month for upgrades) and there enjoy an embarrassment of riches. I’ve already eaten lunch, but I’m given it once again, and since it might be the last hot meal ever offered to a human being on an airplane, I indulge. My seatmate is polite but engrossed in her novel, which is ideal because I hate sitting next to chatterboxes on airplanes, where there is a) no place to hide; and b) no longer any actual silverware with which to stab the loquacious smack in the larynx. With my iPhone and my noise-canceling headphones I can create my own little sanctuary with classical music while I write. I am just about perfectly content in the way of creature comforts, and as I cross the plains I try to be grateful that I’m not a member of the ill-fated Donner party who made this same trip more than a century ago. Despite some of the inconveniences of modern air travel, we’ve come a long way from eating each other, baby.

As much as I try to cultivate these thoughts of gratitude and intentionally return to them, here is the thought that keeps popping in my head without any effort whatsoever on my part: I wonder if I will get upgraded on the way home. It’s humiliating how often that particular thought returns, unbidden, to spoil the moment. It’s one more example of what Phil calls “creeping requirements,” an engineering term for a project’s tendency to become more complex all the time. Creeping requirements rob my gratitude in the moment because I’m always looking ahead to the Next Big Thing.

I’m not alone in this. If we buy the little black dress, we might have a moment of euphoria, but the purchase also necessitates the little black shoes and the silver earrings and perhaps a manicure before the cocktail party. Phil and I have noticed this all summer as our straightforward third-floor bathroom renovation has turned into a full-fledged overhaul of the second and third floors. “While we have the walls open anyway, we should update all of the wiring and bring it to code,” he says. “Also, let’s go ahead and insulate the attic.” (What he does not mention, but which happens: “Let’s be sure to insulate the attic on the hottest day of August, honey! This builds character.”) The bathroom remodeling takes a backseat to the creeping requirements of while-we’re-at-it syndrome. And it all sounds so prudent, so wise to want more.

The Bible talks about not coveting, and I’m intrigued that this commandment comes last of all in God’s Top Ten List. Biblical lists aren’t like our modern lists, where the most important thing usually comes first. Biblical lists often save the best for last: faith, hope, and LOVE, for instance. So it is with the tenth commandment, the most significant commandment of them all, because almost all of the list’s other specific warnings spring from the act of coveting. We’re vulnerable to committing adultery when we look longingly at someone else’s attractive spouse and begin imagining life with that person; adultery begins with covetousness. We’re prone to killing when the victim has something that we want. (At least, it’s always this way in murder mysteries.) And even the commandments against idols and worshiping other gods stem from covetousness, from our susceptibility to whatever golden calves we crave. But can gratitude save me from coveting and creeping requirements?

To be a saint is to be fueled by gratitude, nothing more and nothing less.

—RONALD ROLHEISER

WHAT GRATITUDE IS NOT

Oddly, the root word for “gratitude,” gratia, didn’t start appearing in Christian literature until about eight hundred years ago. That’s not to say that Christians before the High Middle Ages didn’t feel gratitude—they just didn’t wax on about it. In her fascinating cultural study The Gift of Thanks, Margaret Visser writes that although contemporary Americans and some Europeans think that gratitude is ingrained, necessary, and automatic, there are entire cultures where the concept of saying thank you is still largely absent. Some languages have no word for thanks, a fact that’s hard for Americans to wrap our heads around. When European colonizers came to the New World back in the day, they were horrified that Native Americans didn’t thank them for the gifts they brought—because when someone brings you smallpox as a souvenir of their homeland, the least you can do is say thank you.

In contrast, other cultures have umpteen different ways to express gratitude, based on the giver’s relationship to the recipient. In Japan, if someone so much as passes you a salt shaker, you don’t merely thank the giver, but instead launch into a self-abnegating apology for your existence on the planet and your annoying and perpetual need to breathe.

As I’

m reading, I think about Visser’s point that much of what we imagine as authentic gratitude is actually cultural expectation of what a polite, civilized person does. Politeness greases the wheels of society. We make nice. However, true gratitude rarely exists in these automatic, expected formalities. True gratitude is something else altogether.

I’m intrigued by the idea that gratitude is a relatively recent development in Western civilization. This strikes me as ironic, given how in my own experience, gratitude often springs from a remembrance of deprivation. When I get the stomach flu, I’m shocked to realize how quickly a healthy person can become a shaking mass on a chilly bathroom floor. Being sick forces us to recognize the unsung gift of health. But in twenty-first-century America, we enjoy fabulous health and longevity compared to any other time in history. So why are our bookstore shelves littered with titles on the importance of gratitude and the quest for happiness, while our pockmarked ancestors just sucked it up in silence?

Maybe we focus on gratitude because we feel guilty—and scared. We know at a deep level that we’re ludicrously wealthy and healthy. We’re also terrified of that ease and comfort disappearing. So we read books and articles about gratitude as a cardinal virtue not because we feel genuinely grateful, but because we’re afraid of how God might smite us if we don’t. There’s a whole movement centered around “the power of gratitude,” promising that when we say thank you for our blessings, we will “unleash unlimited abundance and happiness.” You can find similar advice in books like How to Want What You Have and Thank You Power and Focus on the Good Stuff. The problem is that this so-called gratitude is actually more about manipulating the universe into giving us even greater blessings than it is about being grateful for the ones we already enjoy. It’s like a kid after a birthday party who only sends Grandma a thank-you card because he’s hoping for a more expensive present for Christmas.

I object to the proliferation of self-help books that promise that gratitude will magically make everything all better. Some years ago when the bestseller The Secret was all the rage, I wrote a blog review so sarcastic that I was contacted by a Dutch journalist who wanted to get the snarky American on camera to declare that merely saying thank you to the universe wasn’t going to alter a person’s reality. The reporter was charmed by the fact that I’d gone back through the diary of Dutch girl Anne Frank to refute the basic premise of Rhoda Byrne’s self-help chartbuster: that only good things will happen to those who think good thoughts, and only bad things will happen to those who think negative thoughts. This pabulum is known as the “Law of Attraction.” In the review, I pointed out how Anne Frank wasn’t exactly spewing negativity with statements such as, “I don’t think of all the misery but of all the beauty that remains,” and, “I keep my ideals, because in spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.” And yet she was victimized, as were millions of others. Their “attitude of gratitude” had little to do with whether they lived through the Holocaust, though some survivors have said that positive thinking helped them regroup and succeed after the war.

Gratitude didn’t save Anne Frank, and it won’t save us. It won’t heal our diseases, make us rich, or bring us fame. We’d love to make gratitude a talisman to magically protect us from disaster, but there is nothing Christian about this; it’s as pagan as the hills to stage-manage the universe into bending to our will. Gratitude is just a gentler way to force the issue, and it’s a lot less messy than, say, sacrificing a bison on the altar. But using gratitude as a carrot to precipitate the universe’s bestowal of a gift is as pagan as the blood sacrifice. If we ever catch ourselves thinking about how God should reward our sunny dispositions with worldly blessings, or imagining that if we’re not grateful for what we already have that God will justifiably withhold further blessings like Santa refusing to bring toys to naughty children at Christmas, then we need to take a long and hard look at what we believe about God. God doesn’t owe us anything, no matter how cheerful and uncomplaining we are. Period.

GRATITUDE FOR CHRISTIANS

It’s clear to me, as I read about gratitude and try these practices myself, that gratitude is not about getting more. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. For an allegedly simple concept, gratitude is surprisingly hard to pin down; I’m much more apt to recognize what it isn’t (a magical panacea, a ticket to expanded blessings) than I am able to isolate what it is. So far this month, I’ve been disappointed by the surface nature of most of the things in my gratitude journal. They’re all so earthy, of this life: I’m grateful that my daughter’s new teachers seem compassionate and caring. I’m grateful for interesting books to edit and to read. I’m inordinately grateful that peaches are in season; in fact, fresh peaches beat out health, home, family, and almost everything else on my list. Including God.

You say grace before meals. All right. But I say grace before the concert and the opera, and grace before the play and pantomime, and grace before I open a book, and grace before sketching, painting, swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing and grace before I dip the pen in the ink.

—G. K. CHESTERTON

Only rarely in my journal do I hit upon spiritual topics. I’m not feeling any wells of gratitude for the things I imagine I should be grateful for—like, say, creation, or Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. I’m pretty much just grateful for peaches. Oh, and sweet corn, also in season. Where is God in my gratitude?

Then I stumble across something beautiful that Thomas Merton had to say about Christian gratitude:

To be grateful is to recognize the Love of God in everything He has given us—and He has given us everything. Every breath we draw is a gift of His love, every moment of existence is a grace, for it brings with it immense graces from Him. Gratitude therefore takes nothing for granted, is never unresponsive, is constantly awakening to new wonder and to praise of the goodness of God. For the grateful person knows that God is good, not by hearsay but by experience. And that is what makes all the difference.

Unlike the earth-bound nature of my own gratitude journal, Merton isn’t focusing just on this life. Christian gratitude has got to be more expansive than the prayers I hear in my church most Sundays, as people thank God for their families, their health, their homes, their jobs, even the weather. There’s nothing wrong with thanking God for those things, but if that’s all we do, it’s like claiming that the prosaic, this-worldly book of Proverbs constitutes the whole of Scripture. There is so much more to Christian experience. When the Bible commands us to be thankful, that gratitude is almost never about us or about the material comforts of our little lives. It’s about being thankful for God and for his “steadfast love” (Ps. 118, 106, 107), not just for what he’s done for us lately.

Merton suggests that every moment of existence can be a grace. I love that because, paradoxically, it takes the pressure off Christians to be so freakin’ happy all the time. If every moment of existence is a grace, we can simply rest in God. It means our joy might just transcend our circumstances. Happiness in the present moment and lasting joy in God are not the same.

I recently saw a quote posted on Facebook by one M. Crane, whose aphorism claimed, “You cannot be thankful and unhappy at the same time.” Within minutes, someone chimed in to say that M. Crane’s maxim was a crock. I silently gave a cheer. Christians absolutely can be thankful and unhappy at the same time. In fact, we ought to be, because this world is not as God intended it. When we are in despair about a child getting leukemia, God is right there beside us feeling righteously pissed. And when we sting with the agony of betrayal, God aches too. The gratitude that Christians feel runs deep because we’re in love with a God who hates cancer even more than we do, and who knows firsthand the throb of treachery.

GRATITUDE RUN AMOK

What’s surprising me about my spiritual practice this month is not that it is easy (did I mention that it isn’t?), but that the simple act of counting my blessings has made gratitude start to feel more natural. Looking for the good, i

t turns out, often does result in finding it—even though I had not expected gratitude to also reveal unsavory aspects of my character and my superficial faith. Despite my inadequacies with this practice—my nicest stationery sits untouched in my desk drawer, as I haven’t followed through with my promise to write a gushy letter of gratitude to someone new every day—I find gratitude spurting up regularly, and when it does, I act on it.

Gratitude smites me at unexpected times, most often in my travels. But it’s not just the fleeting vacation euphoria of new places and people, a break from the usual routine. This well of contentment runs deeper, probably because we began the month by going on vacation to old haunts with long-loved people. There’s nothing particularly new about heading to Lake Michigan with these friends we’ve loved for nearly two decades now, but there’s a world of gratitude in these near-annual gatherings.

When Phil and I were first married, we signed up to be part of a new seminary comedy revue called Theologiggle, never expecting that four of the people we met would become some of our closest friends for life. At first, I was impressed by their humor and cleverness—we cracked ourselves up impersonating seminary professors and writing skits filled with insider jokes about Q, the elusive fifth Gospel.

But these friendships continued to flower long after graduation day. Through the years, our three families have welcomed five children and shared the joys and heartbreaks of trying to figure out how to be quality parents. And when my mom had cancer the first time, Ron and Deb drove five hours each way to visit me at her house, a gesture I still can’t think about without tearing up. Dawn, a pastor, has prayed for me when I didn’t have the words, then enfolded me in life-affirming hugs. We’ve also had hilarity, like when Andrew finished his PhD and the rest of us donned choir robes to knight him in a surprise ceremony with a plastic toy lightsaber and the silliest Viking helmet ever made.

Flunking Sainthood

Flunking Sainthood